While most of India’s computer-related economic success has come via international business opportunities, this story of entrepreneurship is about having struck gold right here in India. Entrepreneurs don’t just seize the opportunities they see; they also create them by understanding needs. In February 2004, Srikant Rao and his partner Ravindra Kini did something of this kind when they established a unique business model, specifically targeting the small and medium enterprise (SME) sector’s business analytics and computing needs: an unusual market in an industry obsessed with big contracts from large international business enterprises.

This shift from established client bases was a result of ‘blue sky thinking’ at the end of lengthy careers spent tending their own and others’ firms. But their biggest source of inspiration has been C.K. Prahalad’s ideation of ‘Bottom of the Pyramid’ (BOP) and ‘sachetization’— terms referring to clients who make up the lowest rung of the economic ladder and hence can only afford to procure products or pay for services in small doses (terms popularized by the sales of sachets of shampoo).

By choosing to service SMEs — organizations that are the least affluent — Srikant and Kini have taken a risk few others would be willing to entertain. Yet their success is testament to the fact that entrepreneurship is more about the spread and nurturing of ideas rather than merely chasing big money.

We meet Srikant and Kini at our offices in the north Bangalore commercial hub of Koramangala. Right on the dot, the first thing that strikes you when you meet the duo is their shared sense of exuberance. As the two take us through their story, we begin to realize the enormous power of simplicity that they have built into their business model. They adopted and incorporated the principles of BOP and sachetization with ease into their business model and created a seemingly new approach to taking the IT business to a resource-poor segment of consumer population.

The passion with which they have built the business is evident in the passion with which they expound their principles. What comes out is their clarity of thought, their patience and dedication as they steered the company through the turbulent initial years. They complement each other well and so their business partnership as well as their personal camaraderie has been a successful one. Without a doubt, they are a team to watch in the coming years.

But before we delve into how exactly Srikant and Kini managed to develop and expand this unique business model, it’s important to understand what brought them to this juncture in life. Growing up, they both remember that even though there was always a strong emphasis on academics, their parents permitted them a degree of freedom that many Indian parents are not known to do. For example, they were often encouraged to participate in sports and other extra-curricular activities. This was often frowned upon in a society that focussed on academic achievement, seen as a direct link to job security. But this socialization benefited them; they grew up with well-rounded personalities and developed crucial inter-personal and social skills that have stood them in good stead throughout their professional careers.

• After fruitful careers spent tending their own and others’ firms, Srikant Rao (left) and Ravindra Kini (right) decided to take a risk.

• They set up a unique business model specifically targeting the small and medium enterprise (SME) sector’s business analytics and computing needs.

• In March 2005, they had three customers. By 2009, they counted over seventy-five small- and medium-sized businesses among their clients.

Kini, one of two identical twins, was born in Mangalore, one of southern India’s famous textile towns. His early education was at Kendriya Vidyalaya and he completed his graduation from MES College, both in Bangalore. Kini attributes his ability to multi-task and get things done to his all-round development while at Kendriya Vidyalaya and also to his early exposure to a professional environment as he accompanied his father to work. Every summer vacation from the ninth class onwards, Kini participated in an internship at his father’s office (a small scale pharmaceutical manufacturing unit in Bangalore).

He claims that this early training gave him a sound foundation in the fundamentals of business management and related operations. On completing his bachelor’s degree in commerce, Kini decided to join his father and supplement the family income. Simultaneously, he pursued a course in cost accounting since he was keen on continuing his education.

In contrast, Srikant’s father was an officer in State Bank of India. This meant frequent transfers from city to city and a new home every few years. Srikant attended schools in different parts of the country — Coimbatore, Chennai, Virudhanagar,Bellary and Bangalore — and remembers very vividly that even though academics were always a priority, his parents would encourage him to pick up swimming, soccer, debating and other such extra-curricular hobbies. After a year at National College, Basavanagudi in Bangalore, Srikant got a degree in mechanical engineering from IIT Bombay. Two years later, he armed himself with a Master of Business Administration (MBA) from IIM Calcutta.

Throughout their corporate careers, both Srikant and Kini have been involved with start-ups and have actively pursued opportunities to set up operations across various sectors and businesses. In these roles, they gained invaluable first-hand experience of how Indian manufacturing industries function. They also learnt how to address the challenges of growth and uncertainty by innovating in business processes at every stage. All this would eventually prove to be extremely critical in their entrepreneurial roles.

More importantly, as Srikant notes, they learnt that ‘the culture in start-up organizations needs to be different; essentially, people need to be encouraged to think and act on their own’. Kini goes on to say. ‘In the context of Indian culture, there is always a tendency to seek approval for everything we do. We tend to look up to some authority figure who we respect to guide us. Nobody says, “Look, this is my idea, I will do it my way, and I know I can do it.” That would be construed as rebellious.’ This aspect of taking ownership and shouldering responsibility is something both of them learnt in their careers in start-up enterprises.

Srikant’s first job, in 1986, was with a TVS Group company—Sundaram Clayton’s railway products division at Hosur. He was among the first management trainees that the company had recruited. Interestingly, the division’s only customer was the Indian Railways. This particular business unit was just three years old at that time and had a start-up feel about it. Srikant chose to begin in the projects division, as he felt that he would get to actually apply his knowledge, both of engineering and management, and also get greater exposure to a number of different functions. To his pleasure, he found that the work was not routine and there were new challenges every day. Most importantly, this business unit provided tangible outcomes, making his professional experience there all the more satisfying.

During his first two years at Sundaram Clayton, Srikant gained extensive experience in various aspects of project management, particularly in managing labour, sales, liaising with vendors, exposure to legal entities in finance, and so on. His biggest takeaway were the lessons in efficiency and elegance in the way that the Indian Railways had developed the ideal systems for planning and implementation, despite its enormous size.

Kini, on the other hand, started his career at the age of twenty-one, as accounts assistant at Karnataka Oilseeds Federation, a quasi state government enterprise, which was also, at that time, a start-up. Established along the lines of the Anand Milk Co-operatives model, it was designed to create an integrated system of production, procurement, processing of oilseeds, and marketing of edible oil and its by-products.

But soon he realized that professional growth in a semi-governmental organization would be slow and restricted, and depended on the number of years of service rather than entrepreneurial promise. The next challenge that the young Kini took on was an assignment as finance manager with another quasi start-up — the Centre for Development of Telematics (C-DoT). Under Dr Sam Pitroda, one of India’s leaders in innovation, C-DoT was vested with full authority and total flexibility to develop state-of-the-art telecommunication technology to meet Indian telecom needs. In this capacity, Kini guided the team which set up processes for computerized accounting, Provident Fund accounting, project accounting, etc.

At the same time, in 1988, a relatively young Srikant, barely twenty-five years of age, was picked to head the materials management function of the railway products division of Sundaram Clayton. It was a major advancement as most others at this level in the company hierarchy were in their late thirties and forties and already had over twenty years of experience under their belts. What’s more, India was then in the grip of inflation and money was tight for all, but Srikant’s job was to ‘keep seven production lines going, as simple as that!’ Three years later, in 1991, Srikant was put in charge of sales for Karnataka and Kerala regions for TVS Electronics, overseeing both direct sales to enterprise customers and through dealers to retail customers.

On sales tours, Srikant discovered something fascinating. He found that his dealers had established their own informal computer components resale channels. Most of the PCs at the time were assembled by neighbourhood computer assemblers who sourced components from the grey market. However, peripherals (like printers and UPS, for instance) were invariably sourced from an established company. Since the buyer would want both as a package, the PC assembler would go around to the dealers, negotiate the best rate for a printer and sell it along with the PC as a total package.

When Srikant noticed this, he thought, ‘Why not formalize this as a business model?’ So he invited the 200-odd assemblers for a dinner along with his dealers and discussed formalizing the rules of engagement — like stocking norms, payment terms, commissions, etc. In six months, Srikant had converted the selling process into a two-tier distribution structure and saw the volume of sales grow exponentially, beating even New Delhi, then the nation’s top market for PCs. Srikant’s innovation in this instance was to go out into the field himself (often riding in the back of an autorickshaw), seek out the business opportunity and create a market where none existed before, instead of waiting for orders from the corporate head office.

Interestingly, after working this long for Indian businesses, Kini and Srikant, independent of each other, made strategic moves to multinational brands.They both sensed that ICT would make a huge impact in India. Kini joined an Australian start-up, Index Computing, which was the software branch of ANZ Bank. He headed the finance department which would eventually become ANZ IT. In this role, Kini gained extensive experience in managing the challenges of exponential growth in terms of headcount and projects, all in an environment that was new to him. His stint with multinational corporations (MNCs) began here, as did the need to work at odd hours due to poor connectivity, a completely new experience. In fact, telecommunication facilities were so poor then that even landline long-distance facilities, never mind mobile phones or e-mail, were scarce and overly expensive.

Around the same time, Srikant too decided that it was time he got exposure to global brands and moved to Microland—a networking company which was in talks with Compaq to be their first distributor in India. The orga- nizational culture here was unique in that the mindset was to ‘question the traditional 20-30 per cent growth rate of tech companies and ask why we can’t expand at 400 per cent year on year’. The only way to accomplish this, according to Srikant, was ‘to think more like a businessman, rather than a sales executive’.

Once this mode of thought was activated, he began to realize that in meetings with clients on future projections, often ‘people didn’t know what they were talking about, and you knew more than others what will happen in two to three years’ time’. This foresight, along with a constantly evolving organizational structure and an open working culture at Microland helped inculcate long-term entrepreneurial traits in Srikant. The fast-paced and ever-changing organizational structure meant that in effect, two years of work experience could be compressed into a three-month time frame.

Another important facet of his executive role in this small business was to benefit from the mentorship of Pradeep Kar and B.A. Raghu. According to Srikant, both these ‘extraordinary managers’ taught him the simple secret of planning and doing. In his words, ‘there is only one way to find out if your plan is right or wrong — by doing’. His experiences illustrate the enormous impact leaders can have in building in-company entrepreneurship. But a recurring problem when taking these risks is that senior, conservative people in the organizational hierarchy are often not on board.

This is where Srikant learned ‘how to fight and take on the politics of an organization’. He identified a senior manager (B.A. Raghu) who was his benefactor and got an assurance from him that if anyone was to impede his work, Raghu would sort it out. Srikant remembers that ‘having these tremendous role models’ who had confidence in him ‘really helped [in shaping] me’. Overall, his memory of his stint at Microland is one of working with a ‘great group’ that was ‘enriching yet fun’.

In the early 1990s, global giant AT&T had just entered the Indian market and was hiring Indian sales managers for the computer business unit of NCR Corporation (which had recently been acquired by AT&T). Srikant was keen to actually work in a multinational company, to gain from exposure to international practices in business. So when a role came up in sales and marketing for AT&T/NCR’s start-up computer business in India, he gladly accepted it. He reflects on the role of serendipity or good luck as a contributing factor in the success of an entrepreneur.

For instance, in 1992, he got a call asking him whether he had a valid passport. And since he did, and the other prospective manager didn’t, he was taken on a business trip to Singapore (his first time abroad). Around

this time, an old acquaintance Shanthi Kumar (from Computer land) joined AT&T in the same business unit as Srikant, and was posted in Hong Kong. Actually, when Srikant had left Microland, he had sent a courtesy e-mail stating his move to AT&T. Luckily, the business plan he conceived for the India business landed on Shanthi Kumar’s desk and this set the wheels in motion in a direction that Srikant had never imagined.

Kumar requested that Srikant come to Hong Kong and help him put together the business plan for the Asia-Pacific region. An original travel plan to Hong Kong of one week eventually stretched to five weeks, including a trip to the US, where Srikant had an opportunity to interact with the NCR manufacturing head, Mark Hurd (who has since been the CEO of HP), and propose some really radical ideas such as setting up a factory in Taiwan and managing distribution from there.

The trip was a success and Srikant moved to Hong Kong to embark on yet another start-up — this one resulting in a business worth $80 million, spread across eleven countries over a span of two years. But by 1996, Srikant recognized that his core competency was India-centric and had the foresight to see India growing as an emerging market. So he decided to return to India to work with NCR, which had by then been divested by AT&T.

At this time, Kini too moved from ANZ IT to NCR India as the business pricing and planning manager. He saw the position as a great opportunity since the NCR India office was just being set up, giving him a chance to institute the India operations from scratch. The move also proved to be a turning point for his entrepreneurial ambitions because this was where he met Srikant for the first time. Kini was handling pricing and planning for all the business divisions and Srikant was the head of the computers division, and the duo — one a sales manager and the other a finance professional — teamed up in a successful partnership that eventually became the basis for their entrepreneurial venture a decade later.

The seeds of their entrepreneurial ambitions were sown early on. For example, one of the software products NCR owned was a transaction server called Top End. NCR sold this particular business to BEA Systems, which owned a competing transaction server called Tuxedo. Between them, BEA Systems and NCR had cornered 80 per cent of the global market share. BEA Systems, at that time, with global revenues of $125 million, did not have any distributors in India. Srikant saw a business opportunity here. He submitted a proposal to BEA to become their distributor in India. They liked the idea and Srikant thought that he now had a business of his own.

But things didn’t exactly work out that way. BEA wanted him to be their country manager (rather than an independent contractor) in India and predictably Srikant protested as, by this point, he wanted to go out on his own. He remembers them saying, ‘It will be like your own business. All we’ll do is to pay your salary for three months and after that you are on your own. We will not carry you beyond that.’ It looked like a fair deal, a sort of semi entrepreneurship offer. He agreed and eventually ended up staying with BEA for six years in that role. Business grew for BEA, both in India and outside, and it went on to become a billion-dollar company. But the urge to be his own boss never really left Srikant.

Kini, meanwhile, declined an offer to move to Sydney while at NCR, and took up an assignment as CFO of a software company in Bangalore. Unfortunately, their plans to go public did not go as planned due to bad market conditions and the unforeseen effects of the 9/11 attacks in the US. With the IT industry not doing so well, Kini did not see an enduring role for himself as a CFO and opted out to take on the role of a full-scale entrepreneur.

It was around this time, during one of their casual conversations, that Kini bounced around the idea of starting up an enterprise with Srikant. Having been friends for over a decade, their families had grown close over time, and the two often chatted about combining their prospects. Srikant remembers vividly that they both came to the realization, almost simultaneously, during a school-related event in which their children were participating, that only if they quit their jobs would they have the drive to see what they could accomplish together. So after a detailed discussion of ideas, they decided to collaborate and formalize their business partnership.

This is where their story gets interesting. Instead of going forward with any business decisions right away, Srikant and Kini decided to do something very unusual. They went on a vacation with their families to the Himalayas! First, they went to Delhi, hired a cab and took off on a tour of the picturesque Himachal Pradesh by road, and then, on an impulse, they extended their holiday and went to Nepal.

When they arrived back in Bangalore after nearly two months, they were well rested and in a clearer state of mind. So now when they contemplated their business prospects, they reached a conclusion: ‘We did not want to be another company in IT or ITES.’

Srikant notes that they agreed on ‘no BPO, call centre or software development. That was certain and very clear. Between the two of us’, he elaborates, ‘we had hands-on experience in all business functions. We had started businesses for others; we had run businesses; we had worked for Indian and multinational companies; we had good exposure to business practices in India as well as overseas. But what should we do?’

Business consulting was a strong option as their business exposure seemed to point in that direction. But if they wanted to operate in the consulting domain, which market should they target? Srikant felt it was ‘definitely not the overseas market, as there were too many players there already, and moreover, the big and well established ones always have an edge.’

So they took a long and hard look at the Indian market. They realized that in this domestic market, the large organizations tended to prioritize branded companies at the expense of smaller companies to do business with. This gave them a clever idea; maybe they should exclusively target SMEs — an enormous yet neglected market with a tremendous upside by way of business potential. Also, this was in tune with their passion to be the change agents impacting Indian SMEs.

As part of their research, Srikant and Kini decided to explore the terrain further and so they drove around southern India —Chennai, Pondicherry, Coimbatore, Peenya, Mysore and Hosur— and met whoever they felt could be of help to them. With the clear objective of understanding the Indian SME segment, they heeded various inputs given by people in virtually all small- and medium-sized sectors, across industries, as well as across states.

They also found that, contrary to what the media was projecting regarding the slow death of SMEs in India, almost every small business owner was in fact talking about making greater investments. So in reality, they were part of a growing market that would only welcome technological help to develop further.

On their tours, they also had the privilege to meet some ‘senior gurus’ in the field, as Srikant likes to refer to them. Most notable among these teachers are Prof. Sadagopan, Prof. Deepak Phatak and Prof. Ashok Jhunjunwala. Speaking to these leaders revealed that the IT industry’s biggest focus while trying to address the needs of small- and medium-sized businesses was ‘affordable computing’. Issues of cost and connectivity were topmost on the minds of IT vendors. This posed questions such as: how to bring the cost of PCs from Rs 30,000 ($750) down to less than Rs 10,000 ($250)? Or else, how to secure a reliable and affordable broadband connection?

With costs of technology being increasingly lowered, Internet access becoming easier and business prospects growing, Kini and Srikant decided that their new venture would be focussed on tailoring a business package specifically to be utilized by SMEs. It was certainly an advantage that nobody else was really looking at the SME market. Srikant and Kini reasoned that here lay a virgin market with great untapped potential. The trick to turning it into a business opportunity lay in combining low-cost computing and telecommunication with niche business consulting solutions that help stabilize the decision-making cycle.

But to be fair, there was a measure of scepticism as well. Among the sceptics were many SME owners who bluntly voiced their concerns: ‘You two have worked for multinational companies until now. What if somebody offers you a fancy salary? If you take up such an offer, wouldn’t that leave us in the lurch?’ Kini recalls. ‘One of the earliest things that we had to do was to convince our prospects that we are here to stay, and are not going to run away.’

But their biggest revelation came when they had the privilege of meeting and interacting with C.K. Prahalad in 2005. The professor from Coimbatore had popularized the BOP and sachetization concepts. From him they learnt that that there are tremendous benefits to companies who choose to serve these markets in ways responsive to their needs. Things just clicked for Srikant and Kini at this point, aided no doubt, by their keeping an open mind and disregarding the various criticisms cast on Prof. Prahalad, calling him an out-of-touch academic.

Generally speaking, the dominant assumption is that the less affluent are not brand-conscious. But on the contrary, they are very brand-conscious and also extremely value-conscious out of sheer necessity to save every last paisa or penny. Also, contrary to the popular view, BOP consumers are busy connecting and networking with others. They are rapidly exploiting the benefits of mobile information networks, and again, due to necessity, accept advanced technology readily.

But in order to convert the BOP into a consumer market, one has to create the capacity to consume. This is based on three simple principles — affordability, accessibility and availability. Sachetization, or the bundling of goods and services into small, cheap and readily available packages, is the answer to creating the capacity to consume. So in short, the idea that SMEs would not pay for quality was a myth. In fact, their scepticism was a result of their experiences with a few dodgy IT vendors who had sold them hardware and software and then not provided the necessary post sales support and back-up.

So the conversation with Prahalad helped Srikant and Kini focus their thinking on the SME sector in India. The concept of BOP fitted neatly into the needs of this segment. Here they clearly saw the need for IT, telecommunication, business software and business consulting, all put together in an affordable package — the very sachetization that the professor recommended.

The secret was to achieve large-scale operations without sacrificing quality. Essentially, if Srikant and Kini could price their services in a way that the client saw their value deepen over a period of time, then they would have a workable business model. Affordable Business Solutions (ABS) was born — replete with the logo indicating a triangle representing the pyramid.

Next, they began looking at the most widespread applications of sachetization and found that these were generally in government financed welfare projects and with NGOs, for example, in e-learning, education, health care for rural market, etc. However, their intuition told them that a recipient who pays for services will value them more and in turn not create a dependency syndrome where he expects things for free always. Having done their homework diligently, ABS saw three areas where they could provide value to customers in the SME segment—IT, education and business consulting.

IT was the easiest of the lot. The IT giants had no interest in addressing this segment by themselves, focussing only on the large enterprise market. Either they did not understand the SME segment at all or they did not want to address it from the point of view of value added to their businesses. ABS’s challenge was to get major businesses to buy in, but they knew that the traditional route would probably not work.

So they went to IT vendors like Microsoft and IBM and said to them, ‘Look, you are not looking at these SME markets for some reason. If someone does approach you, he has to buy your software with licenses for each user. On top of that, he has to pay for the hardware, networking and maintenance contract and even has to pay implementation partners to help him set up his IT operation and run it. The very thought of spending so much upfront will deter him from proceeding further with you. But he does need IT support. So he goes to the grey market, buys hardware at much lower prices, gets pirated software and gets his IT set-up operational on his own, albeit not very efficiently. Does he like doing all this, does he like using pirated software? The answer is always going to be a ‘no’. The vast majority of people we have spoken with don’t want to deal with this mess. But they have no choice as your prices are simply not affordable.’

So ABS proposed an alternative model to them, explained here in a highly simplistic way. Suppose the branded software along with the networking and hardware products costs $20,000 (Rs 10,00,000) plus $5,000 (Rs 2,00,000) per year for maintenance and upkeep (after the first year). Over a five-year period, the cost totals $40,000 (Rs 20,00,000). Divided into sixty monthly segments, that comes to $667 month (Rs 33,333). This is where sachetization comes in. ABS asks the customer to pay them $700 (Rs 35,000) per month instead and in return gives a package of services, which will include hardware, software and maintenance; essentially everything to improve his productivity in business. The small business owner only pays a small amount on a monthly basis for a service that he is getting, not a product, and as long as he sees value in it, he continues to pay for the services. For him, there is no large upfront payment; he does not have to pay for each individual service and he does not have to maintain the equipment.

For their part, ABS proposed hosting all the software on their servers, from which the SME owner can access their applications through the Internet. Obviously they have built in enough security into all the transactions, and moreover, the pricing structure is utility based. Their thinking is aptly summarized by Srikant: ‘As long as I have a satisfied customer, I will continue getting the money.’

ABS has a leasing arrangement with its suppliers, IBM, for example, for the equipment towards which they make monthly payments. So, despite possessing capital equipment, ABS is only paying monthly and does not incur heavy cash outflow upfront. The software vendor, Microsoft, for instance, assigns ABS a service provider’s licence to rent out the software to any number of customers. This is not allowed under a normal licence. In fact, ABS has to send a monthly statement detailing how many customers they are leasing to, and based on that, they pay a licence fee.

Overall, Srikant explains, ‘What could have been an initial investment of hundred thousand rupees for the SME owner has now become a few thousand rupees per month. The vendors are happy because they get more over a five-year period and the customers are happy because they get all the IT-based services they need at a monthly fee and there is no long term risk for them.’

This application of the principles of BOP and sachetization to IT is now called SAAS by the industry, an abbreviation for ‘software as a service’. By default, ABS are the pioneers of SAAS, and Srikant and Kini are often invited to address seminars on this innovative concept. A direct example of this model in action is a small company called WildCraft. With eighteen stores spread over India and a factory in Bangalore, they desperately needed an affordable solution to their distributed accounting and inventory control processes. The costs of carrying too much inventory was cutting into the money needed for their own growth. By opting for the services offered by ABS, Wildcraft has been able to manage their inventory and finances and embark on an exponential growth path with absolutely no capital expenditure.

Speaking of services, Srikant and Kini bring up the two other areas of ABS’s expertise — education and business consulting. In the education domain, ABS has created a curriculum consisting of a number of small modules in many functional areas. These constitute a formal skill upgrading application for people learning on the job, and depending on their need, these modules are used for educating personnel in English or the local language such as Tamil, Kannada, Telegu, etc. The courses are also offered in remote areas and at convenient timings (evenings and weekends) so that their accessibility is maximized. At this stage, ABS has very consciously avoided e-learning because they feel it is not very effective.

In their business consulting suite, ABS offers services across functional areas for an extended period — a sort of ‘virtual manager’until almost all functions can be covered internally. This is usually an eighteen-month period up to a point where a company becomes self-operative. This total offering —IT services, education and business consulting — has now been termed as ‘business transformation’.

Srikant and Kini’s amazing journey and experiences make their thoughts on entrepreneurship and the qualities required to succeed in business extremely valuable. Srikant often uses visualization to describe the process of imagining their entrepreneurial journey. Visualizing here means speculating on what will happen down the line in two/three/five years from now; what are market expectations; changes in the environment; which sectors will shape up to have an impact, and so on. Also critically important, as they put it, ‘is how quickly you can translate an idea into a business plan and how quickly you move from the strategizing and planning stage to the action stage without stopping to cross every t and dot every i.’ The difference becomes apparent when we glance at their individual careers, where their roles have always been less structured — in start-ups, there were no set rules. The markets were new and they had to invent their own rules. They were clear in their concepts, but these had to be put into a new perspective in order to succeed.

We couldn’t help wonder if his education at an IIM contributed to Srikant’s becoming an entrepreneur. Not directly, he explains. Back then, it was not covered in the curriculum and nobody thought of entrepreneurship as a career path. The objective was to get a job in a premier Indian blue chip company and move up the hierarchy. The success stories of leadership that were discussed were about leaders and executives in large companies, not entrepreneurs.

One didn’t really have role models. Which brings us to the type of ‘associates’ hired at ABS; Srikant and Kini do not like to call them employees. ABS does not specifically look for people with fancy academic qualifications and prefers to hire personnel with some functional experience in an SME. They have experimented successfully with women who had taken a break in their careers for whatever reason. Srikant and Kini offered them part-time employment and flexible work hours.

In HR terms, the bonding among the employees is strong. Several of the personnel are from small towns, are fired up to prove their worth, are generally more ambitious and interact well with the SME customer base. Srikant has a very interesting story about how he gained his first customer. ‘This was in August 2004. Seetharamiah, one of the first people we met after conceptualizing ABS, is a doyen of the automotive components industry in Chennai. “Who are your other customers?” he asked us. “No one; you would be our first customer” was our honest answer. “Fine. You are on,” he said, “because you will ensure that the project will not fail!”

In the period between June 2004 when they began and March 2005, they had three customers. In the following year, they got twenty customers and the year after that, fifty customers. By 2009, they counted over seventy-five small- and medium-sized businesses among their clients—cutting across multiple industry verticals: auto-component, fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG), electronics manufacturing, agro-business, chemical companies, retail stores and pharmaceutical businesses.

In fact, Srikant states, ‘We don’t have any sales representatives. Our customers refer us to others. In Mysore, for example, we started off with two customers; now we have ten. We have a presence in practically every vertical. If each customer refers us to three prospects at CEO level, we are sure to sign on at least one. So a 100 per cent growth year on year is pretty much guaranteed!’

Kini testifies that his priority is to expand, but within their means. He is also not keen to borrow or raise equity — only to utilize internally generated funds so as to mitigate risk. Another key issue is to keep attrition under control. For him, ‘Retention of people is always a challenge. We have a leadership programme in which we mentor our fast-track associates and offer them more opportunities to develop themselves. We have told them that in three years, they should no longer be on anybody’s payroll but should be running independent businesses; perhaps as our franchisee or as their own affordable business.’

In fact, ABS is now going to university and college campuses and telling students about the concepts that made their business successful. During these visits, they urge students ‘to take this up, not as a career, but as entrepreneurs’. This is the model that ABS is now propagating. Srikant estimates, ‘The way ABS can grow is to have centres in each of the 480 SME clusters in India — across industry and across geography. If each cluster can have fifty to hundred customers, that’s our growth path.’

Based on their unique business model, ABS has evolved an exceptionally innovative concept that they call ‘reverse franchising’, which they intend to launch in the near future. In this scheme, the small-scale entrepreneur is fully equipped by ABS to start a business in terms of covering all upfront expenses related to office space, salaries, marketing costs, equipment, training, and so on. The entrepreneur makes no initial investment whatsoever and is fully supported for three years by being given a nominal salary during this period. Once the risk is mitigated and the business is running well, the entrepreneurs have to start paying a royalty to ABS. With the software and hardware support provided by ABS, the entrepreneur avoids having to deal with every single vendor and can focus instead on the task of running and growing the business.

But who would make an ideal combination for an entrepreneurial team? The ABS model has some very definite answers. The ideal team would consist of three specializations — one from a commercial background, one from finance and one from manufacturing. It is beneficial if they get along well with each other, especially if they have little or no prior experience. As for individuals, the duo identify three critical traits for success — enthusiasm, willingness to work hard and an innovative approach to work and life.

Beyond this, Srikant and Kini identify three questions all potential entrepreneurs must ask themselves prior to starting a business. ‘First, ask yourself why you want to be an entrepreneur; is it a fad; is it because you are frustrated in your job, or you don’t like your boss? What is your motive? Be very clear about this. If you say that it is to make money, that’s fine, but remember that money is a means to an end. What is the end that you are seeking? Second, what is your lifestyle now? Critically examine this — what are your needs and what are the things you can do without? Set aside enough resources to see yourself through two or three years. Negotiate all this with your spouse, your children, and with the immediate family because you will constantly need their support. Most important, negotiate this with yourself and freeze on this, otherwise you may mess up your life. Third, really understand what your customer wants. Remember, you are addressing a customer’s need.

Ask yourself, ‘Do I have something which the customer is willing to pay for?’ and offer that. Stick to your core competencies, and make sure that they differentiate you from others.’ For example, Srikant’s core competencies include managing relationships, as is evident from his successful dealings and negotiations with organizations like IBM and Microsoft among others. Kini’s core competence is managing projects. He is able to visualize very well, yet at the same time, he can go into minute details and micro-plan what needs to be done, by whom and when. In short, he has learnt to prioritize his tasks, manages his time well and knows exactly what he can and cannot delegate.

At the end of the day, Srikant and Kini’s story is about two successful Indian entrepreneurs who took the risk, stuck to their values and fielded the challenges courageously. Their story could have been very different but for their innate self-confidence, certainty of purpose and perseverance. While many others in their positions would have chosen to remain secure in senior posts at an MNC, Srikant and Kini decided to partner with each other and strike out in uncharted territory.

Prior to doing so, they both accumulated valuable business expertise in various capacities and brought this knowledge and experience to the table while founding ABS. And by choosing to serve a market that comprises the least wealthy of India’s business population, ABS is not just promoting a business, it is genuinely addressing a need that many have passed by. India’s many small businesses and medium-scale industry sectors underscore this point. The enterprising duo prove once again that it is ideas that make a business great, not the amount of money there is to be made.

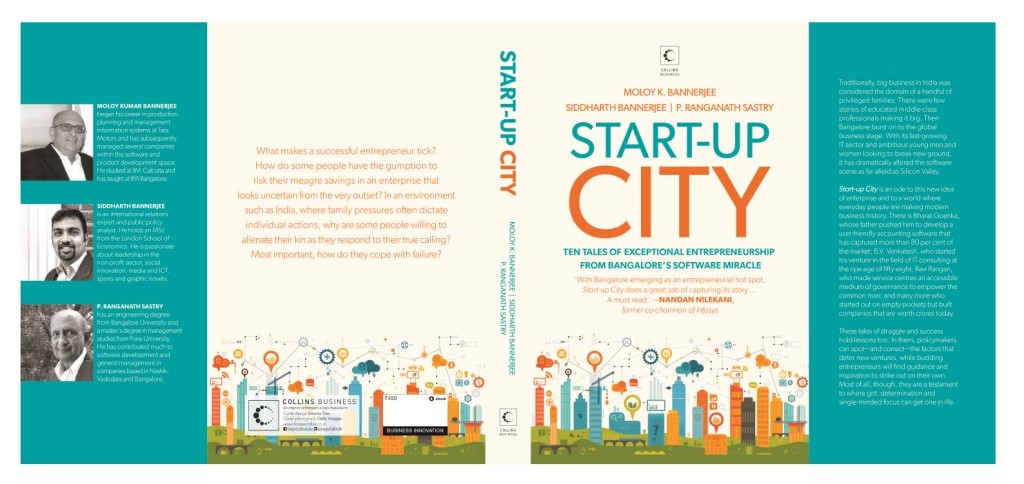

[This piece has been extracted from ‘Start-up City: Ten Tales of Exceptional Entrepreneurship Bangalore’s Software Miracle’ by Moloy Kumar Bannerjee, Siddharth Bannerjee and P. Ranganath Sastry. The book was published by Collins Business, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers, India, in 2014. It is available for purchase on Amazon.in as a Hardcover and Kindle edition. Author profiles are as follows:

Moloy Kumar Bannerjee is a graduate of Indian Institute of Management Calcutta, batch of 1968. He started his career in production planning and management information systems with the Tata Motors group in Mumbai, where he worked for nine years. He then moved to Bangalore and briefly taught operations management and systems design at the IIM there. Over the past thirty-odd years, Moloy has managed several companies (in India and abroad) within the software and product development space. He has a keen interest in philosophy and history and has lectured on and published papers about India’s samkhya and yoga philosophy traditions.

Moloy Kumar Bannerjee is a graduate of Indian Institute of Management Calcutta, batch of 1968. He started his career in production planning and management information systems with the Tata Motors group in Mumbai, where he worked for nine years. He then moved to Bangalore and briefly taught operations management and systems design at the IIM there. Over the past thirty-odd years, Moloy has managed several companies (in India and abroad) within the software and product development space. He has a keen interest in philosophy and history and has lectured on and published papers about India’s samkhya and yoga philosophy traditions.

P. Ranganath Sastry has an engineering degree from BMS College, Bangalore University and a postgraduation in management studies from Pune University. His career began at Hindustan Aeronautics in Nashik, spanning management systems and quality assurance. He then spent five years as a faculty member at the HAL Management Academy in Bangalore teaching operations management and information technology. For the past twenty-five years, Ranganath has contributed much to software development and general management in companies based in Vadodara and Bangalore. His current interests include the study of Vedic philosophy, mentoring of students, lecturing on management systems at management institutes, and exploring the impact of technology on urban and rural life.

P. Ranganath Sastry has an engineering degree from BMS College, Bangalore University and a postgraduation in management studies from Pune University. His career began at Hindustan Aeronautics in Nashik, spanning management systems and quality assurance. He then spent five years as a faculty member at the HAL Management Academy in Bangalore teaching operations management and information technology. For the past twenty-five years, Ranganath has contributed much to software development and general management in companies based in Vadodara and Bangalore. His current interests include the study of Vedic philosophy, mentoring of students, lecturing on management systems at management institutes, and exploring the impact of technology on urban and rural life.

Siddharth Bannerjee is a social entrepreneur who wears many hats, including as an international relations expert, public policy analyst and social research practitioner. He has published academic texts, commented on TV/radio and blogged on the subjects of civil society leadership, economic development and global governance reform. Professionally, Siddharth has worked as Director of Research at the Association for Canadian Studies and spent a year as a McGill University–Jeanne Sauvé Foundation Fellow for emerging young leaders, both in Montreal, Canada. He holds an MSc degree from the London School of Economics and is passionate about the non-profit sector, sports, social media, ICT and graphic novels.]

Siddharth Bannerjee is a social entrepreneur who wears many hats, including as an international relations expert, public policy analyst and social research practitioner. He has published academic texts, commented on TV/radio and blogged on the subjects of civil society leadership, economic development and global governance reform. Professionally, Siddharth has worked as Director of Research at the Association for Canadian Studies and spent a year as a McGill University–Jeanne Sauvé Foundation Fellow for emerging young leaders, both in Montreal, Canada. He holds an MSc degree from the London School of Economics and is passionate about the non-profit sector, sports, social media, ICT and graphic novels.]