She would read to me from Marathi storybooks we would buy from the local stationery shop, slim offset printed books with two-colour illustrations. The book-buying was a ritual I looked forward to, we would go to the tiny shop on the busy road opposite my grandfather’s old four-storied Wada. One couldn’t enter the shop but had to stand on the street and ask for whatever one wanted. Dhumne Master’s store was painted blue and he had many jars of sweets and candy, pencils, erasers, notebooks, small diaries, schoolbooks, storybooks, sharpeners and little plastic toys.

Cult Fundaes

I believe, introducing ‘Art’ has been one of the most challenging tasks of our education, as it involves exploring one’s ‘creativity’ and while doing this, one has to be utmost cautious about not harming the very purpose of this exercise.

As such, I was never formally trained in sketching/drawing. Whatever happened during my school days under the garb of art classes, can, at best, be termed as ‘learning on your own’ without getting even the rudimentary introduction/guidance, which I wish to provide here.

Books are the windows to fantastic and magical worlds! Keep the windows open!” Children who read grow up to become adults who think.

Illustration 1: Nabagunjara Patachitra painting by Shri Kalu Charan Barik. Photo credit: Abhimanyu Barik

The Patachitra traditions of Odisha are replete with artistic, cultural, and symbolic connotations. The stories from the eighteen Mahapuranas, Upa-puranas, Mahābhārata, and other epics are the core of the Patachitra lineage in Odisha. These tales from the oral or the verbal classical and folk traditions when translated into the visual medium through art, become richer and highly emblematic. Imaginative terrains associated with these artistic mediums have storytelling as their central motif. There have been several discursive papers, books, and reflection articles that narrate the stories that are depicted in Patachitras, and of late there is a renewed interest in the Puranic stories especially those concerning animals and their interpretations in paintings and other new mediums. This article focuses on one such aspect of the Patachitra’s storytelling tradition which is a recurrent motif in several paintings made in this style from the ancient times to its contemporary expressions – the story of the Nabagunajara (in colloquial Odia) or the Navagunjara besa (form/attire). Over the past decade, there has been a massive interest in understanding the story of the Nabagunjara. Devdutt Pattanaik created popular interest in the word Nabagunjara with a brief mention of the tale in his book Indian Mythology: Tales, Symbols, and Rituals from the Heart of the Subcontinent (2003). There has been a persistent interest in the Internet world to narrate the symbolic as well as the artistic meanings concealed within the story of the Nabagunajara. Stray articles with limited research have been circulating on the Internet with half-baked reflections on the Nabagunjara.

The battle of Karbala was fought in the desert of Karbala in central Iraq in 61 AH (680 AD). During the Karbala battle, the Shia leader and Prophet Muhammad’s grandson, Imam Husayn, along with his family and troops, was tortured and killed by the troops of the Sunni leader, the Umayyid caliph, Yazid. The tragic climax of a long-drawn war of inheritance between the prophetic line and the caliphate, the martyrdom of Imam Husayn and his family is commemorated during the first month of the Hijri calendar, Muharram. The Karbala ritual, as this kind of commemoration has come to be called, was first institutionalised by the Buyid dynasty in tenth-century Iran. From there, the ritual has spread far and wide throughout the Islamicate world, including in Bengal, which before the Partition of 1947 was a Shia-minority region.

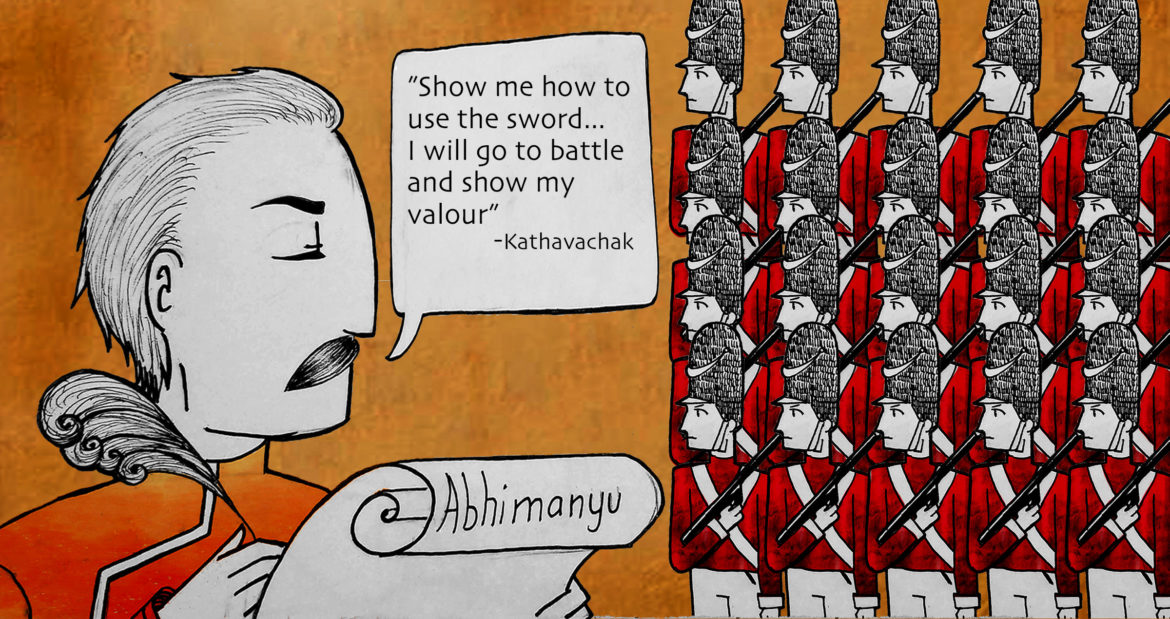

Mythology in the Modern Age

Guided by the hands of Reason and Science, one would imagine the modern age has little place for endless epics, speculative reflections and metaphysical meanderings. While Mythology may have occupied centre stage in times of yore, one may well ask what place it has in today’s world. The answer is more complex than it appears.

One area where Mythology has wielded a heavy hand is during the Indian Freedom Movement. From influencing the methods and philosophy of leaders like Gandhi and Tilak, to providing a subject upon which artists built nationalist visions, Mythology became the guiding force of History.

jñānānandamayaṁ devaṁ nirmalasphaṭikākr̥tim ।

ādhāraṁ sarvavidyānāṁ hayagrīvam upāsmahe ॥

This is a prayer that children, especially in a vaishnavaite home, are taught to recite before embarking on any learning activity. Knowledge is held on a high pedestal all across the globe. And the Indian tradition acknowledges this great value of knowledge by paying respects to the divinity associated with this facet of life by offering verses of praise and worshipping through rituals and festivals.