I chatter, chatter, as I flow

To join the brimming river,

For men may come and men may go,

But I go on forever.

When I was in primary school, I read a poem about a brook that chattered merrily as it marked its course through hills and dales. The brook’s merry song was punctuated with a somewhat cheeky refrain that went like this: although the human life is transient, its own flow is perpetual. This refrain stuck with me. With the naiveté of a school kid, I wondered how long would that forever be. In that moment, I also intuited the meaning of the word eternal – the brook would never cease to flow and would outlast generations of us.

With more years behind me now, I’ve come to realise that the natural world or nature is not exempt from the law of mutability that governs all living, breathing forms of life. It is a known geological fact that extinction is a natural process. Once formed all natural objects be it mountains, lakes, streams, or rivers do not stay the same. Like us, they pass through a cycle of youth, maturity, old age, and death. Water bodies, even the largest ones, slowly disappear as their basins fill with sediment and plant material. However, this natural aging of water bodies happens very slowly, over the course of hundreds and even thousands of years. Hence, the brook’s boastful claim “I go on forever.”

It is a known geological fact that extinction is a natural process. Once formed all natural objects be it mountains, lakes, streams, or rivers do not stay the same. Like us, they pass through a cycle of youth, maturity, old age, and death.

But the brook’s song was sung before we humans started leaving our ugly footprints all over nature. Since then, we have distorted the natural landscape in a lot of ways: we have melted glaciers, reclaimed wetlands, drained rivers, razed mountains, deforested sprawling acres of woodland, quarried hills, and transformed nature into a useless sump in which to dilute our waste. That our actions have jeopardised the endless, blissful existence of an unknown brook is the least of our concerns because it feels more god-like to be able to engineer the destiny of the natural world, to dictate who shall live and for how long. So, we march on relentlessly replacing wild, raw nature with crafted, artificial landscapes.

Our Own Backyard

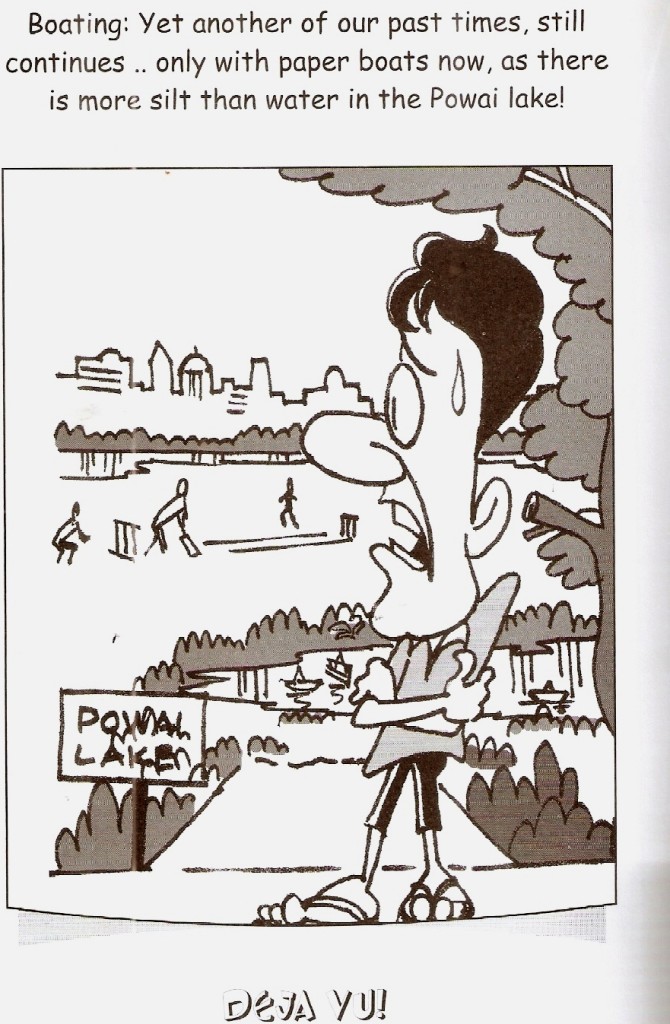

For those of us who live in the IIT Bombay campus, we have a 520-acre lake in our backyard. This lake forms a soothing backdrop to all our academic, professional or domestic pursuits. We walk by it. We walk our dogs by it. We savour the fresh air that rushes into our lungs each time we take a detour through the narrow road that winds by the lake. While yapping with friends, we watch the sun go down from the steps of the Institute’s guest house that commands a magnificent view of the lake. We marvel at the bobbing silhouette of an occasional angler as he adroitly guides his tyre across the waters without paying any heed to the reptiles that lurk beneath. We delight at the sight of gliding eagles as they trace their trajectory over the lake soaring higher and higher. We photograph the lake and the wildlife that thrives on its waters. On clear days, we take pleasure in the glorious sunset that paints the sky above the lake in a riot of colours. And, in-between enjoying these idyllic moments, some of us wonder if the rapidly advancing beds of weeds will take over the lake, if the BMC’s latest rejuvenation efforts will deliver lasting results or if the cattle that graze on the overrun shorelines will eventually displace the herons, kingfishers, cormorants and crocodiles that call the lake their home.

For those of us who live in the IIT Bombay campus, we have a 520-acre lake in our backyard. This lake forms a soothing backdrop to all our academic, professional or domestic pursuits. We walk by it. We walk our dogs by it. We savour the fresh air that rushes into our lungs each time we take a detour through the narrow road that winds by the lake. While yapping with friends, we watch the sun go down from the steps of the Institute’s guest house that commands a magnificent view of the lake. We marvel at the bobbing silhouette of an occasional angler as he adroitly guides his tyre across the waters without paying any heed to the reptiles that lurk beneath. We delight at the sight of gliding eagles as they trace their trajectory over the lake soaring higher and higher. We photograph the lake and the wildlife that thrives on its waters. On clear days, we take pleasure in the glorious sunset that paints the sky above the lake in a riot of colours. And, in-between enjoying these idyllic moments, some of us wonder if the rapidly advancing beds of weeds will take over the lake, if the BMC’s latest rejuvenation efforts will deliver lasting results or if the cattle that graze on the overrun shorelines will eventually displace the herons, kingfishers, cormorants and crocodiles that call the lake their home.

Yes, at a little over 100 years of age the Powai Lake is already past its prime. With a fast receding shoreline, a heavily silted bottom and dropping water levels this lake in our backyard is at the brink of an ecological collapse and aging faster than it should. More worrisome is the fact that the lake is choking and possibly dying.

Is there any hope of eternity for the Powai lake?

How Green Was My Valley

Yet even a few decades ago the condition of the lake was very different. Prof. Arun Inamdar of the Centre of Studies in Resources Engineering and an IIT-B alumnus, wistfully reminisces how in the 70s the lake used to be full brimmed and almost without a single trace of weed. When first visiting the institute as a prospective student from Sholapur, he recalls being awestruck by the undulating expanse of blue that lapped at the shores of the Institute. This blue panorama was a delight to his eyes, a unique spectacle for one who had been accustomed to an arid landscape. And, in that moment he made IITB his alma mater choosing it over other institutes in which he had been offered a seat. The institute’s technological prowess, he notes with a quiet laugh, was a secondary consideration. It was the lake that made him fall in love with the Institute.

At a little over 100 years of age the Powai Lake is already past its prime. With a fast receding shoreline, a heavily silted bottom and dropping water levels this lake in our backyard is at the brink of an ecological collapse and aging faster than it should. More worrisome is the fact that the lake is choking and possibly dying.

This youthful face of Powai Lake changed when the land around its catchment area was released for real estate development in the 80s and 90s of the last century. Until then the land which held the lake in its quiet embrace was mostly unspoilt except in patches where it was tilled. Now the prolific builder arrived with his formidable arsenal of excavators, cranes, pavers and road millers to tame the wilderness. He started lopping trees, clearing the undergrowth, paving green hills and drawing out the water from the lake for the construction activities. Slowly but steadily plush residential towers reared their heads all across the landscape; towers that are coveted for their gorgeous view of the lake. Next, roads were developed to support the influx of people in this area. And, like this one act of construction led to another converting the Powai region into an upmarket commercial and residential hub.

The Powai Lake still stands at the centre of all this new grandeur. In fact, it itself is the centrepiece. It still continues to mesmerise the old and the new who live around it. Birds still fly across its horizon. Crocodiles still swim in its waters. The sun still sets on its horizon. But, there’s something else happening too. The once scenic lake is today smothered by floating beds of hyacinth and slimy green algae, caked with silt, and saturated with pollution. In comparison to the full-brimmed spectacle of the 70’s, the lake is today a mere shadow of itself.

How did the picture change within such a short span of time?

Standing on the Brink

Of all the different factors that have contributed towards the diminution of the Powai Lake, Prof. Inamdar considers silting and pollution to be the worst culprits.

Image Courtesy: Prof. Arun Inamdar

When the land around the Powai basin was reclaimed and built over, large swathes of woodland were cleared to make way for new buildings. This deforestation accelerated soil erosion around the margins of the lake, the bulk of which was deposited at its bottom. In addition, the silt churned by the construction sites also found its way into the lake making it shallower and reducing its intrinsic capacity for storing water. Prof. Ina

mdar cautions that a rise in the height of a lake bed can have several negative ramifications. First, aquatic life depends heavily on the supply of fresh water that exists in lakes; reduced volume of water means less dissolved oxygen and less living space for the biota. Secondly, a rise in the floor level also means quick overflow that can potentially lead to flood conditions. As a geologist would explain, apart from anchoring soils, a forest cover acts as a sort of sponge that releases water at regular intervals. The loss of forest cover creates impervious surfaces allowing more runoff to flow rapidly into streams, rapidly elevating water levels and subjecting downstream settlements to flooding. And this is exactly what had happened in 2005 when Powai began to overflow and discharged thousands of litres of water into the Mithi River.

The once scenic lake is today smothered by floating beds of hyacinth and slimy green algae, caked with silt, and saturated with pollution. In comparison to the full-brimmed spectacle of the 70’s, the lake is today a mere shadow of itself.

During the dry season, the scenario in the Powai basin is completely different; areas downstream of deforested land are prone to months-long drought. This is because the streams of natural runoff that would earlier flow into the lake have been either cut off because of the development work or are bringing less and less water to the lake each year. That this rain-fed lake is gradually shrinking is perceptible not only from its fast reducing shoreline but also from the way its waters hit the bottom within months of monsoon turning vast stretches of the lake into cricket ground or

grassland for cattle. The lake is therefore impacted in two major ways: on one hand, sedimentation has decreased its water storing capacity; on the other hand the sources of replenishment (in the form of monsoon rainfall or natural run-off) for this lake have dried up due to heavy deforestation and urbanisation in its catchment area.

Another huge source of worry is the pollution. This presence of pollutants in the lake is evident from the colonies of water hyacinth and other aquatic weeds that have taken over vast portions of the lake. Not only does the process of development contaminate our environment but the developed land in turn becomes a perennial source of pollution both by its structures and the lifestyles of people living in them. In the instance of the Powai basin, the act of development has created new pockets of habitation that now routinely release sewage and industrial waste into the lake; a problem that is aggravated by the declining vegetation cover in the surrounds of the lake. The positive benefits of shoreline vegetation go beyond preventing soil erosion or maintaining the precipitation levels in a region. The natural vegetation cover around a water body also acts as living filters of pollution by capturing soil sediment, chemicals and other pollutants that may be present in the runoff that flows into the lake from the human settlements on its banks. Reduced shoreline vegetation allows the runoff to enter the lake directly without undergoing this natural filtration process. The pollutants that enter the lake thus disrupt the natural balance of the water creating an

environment suitable for invasive aquatic plants.

The Road Not Taken

Image Courtesy: Prof. Arun Inamdar

When faced with the imminent threat of an overwhelming environmental issue such as a dying lake, the tendency is to engage in a blame game by either pinning the onus on a group of individuals or by attributing the accountability for ecological degradation to an institution. Out of despair, we censure the real estate developer for marauding the virgin land or the hotel owner for flagrantly violating the pollution control guidelines; lambast industries for not treating their waste or the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) for not trying harder. But that hardly takes us anywhere and certainly does not save the lake. At the end of day, we are all collectively responsible because this defilement affects us even when we have no personal accountability.

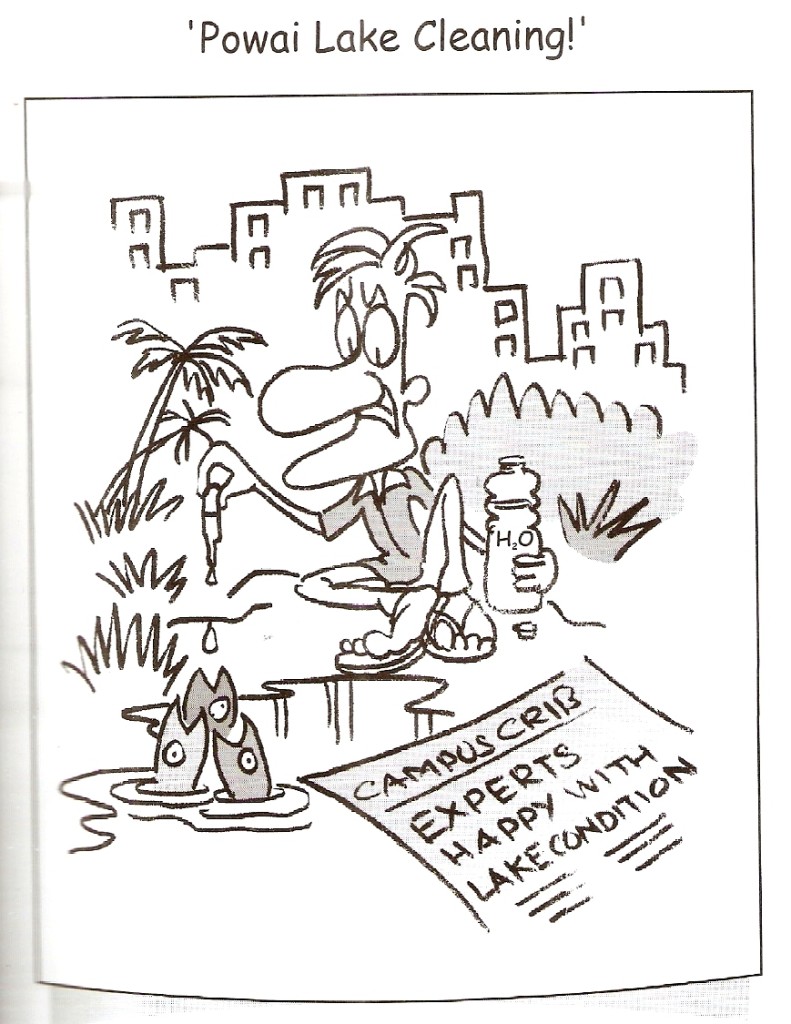

However, in the case of Powai Lake indifference or lack of awareness is not an issue. Strange as it may sound, the stakeholders of the Powai Lake — the developer, the resident, the industries that draw water from the lake, the IITB Heritage Foundation, the BMC that owns the lake — are not entirely apathetic to the plight of this ailing lake. We all care for the lake to a greater or lesser extent. How else do we explain the money worth lakhs of rupees that the BMC has liberally poured into the lake or the volunteering work that has been done from time to time to cure the ailing water body? In fact, Prof. Inamdar takes a moment to recall the effort made by the IIT-B Class of 1980 to rejuvenate the lake. Yet surprisingly we have very little to show for our labours apart from a well-paved promenade along the shore, a couple of parks, and a musical fountain at the lakefront that is played twice each evening.

The correct question to ask is not if we are interested in saving the lake but if our endeavours match the scale of the problem? Are we making a sustained effort in the right direction? And, most importantly, are we thinking and working scientifically?

When faced with the imminent threat of an overwhelming environmental issue such as a dying lake, the tendency is to engage in a blame game by either pinning the onus on a group of individuals or by attributing the accountability for ecological degradation to an institution.

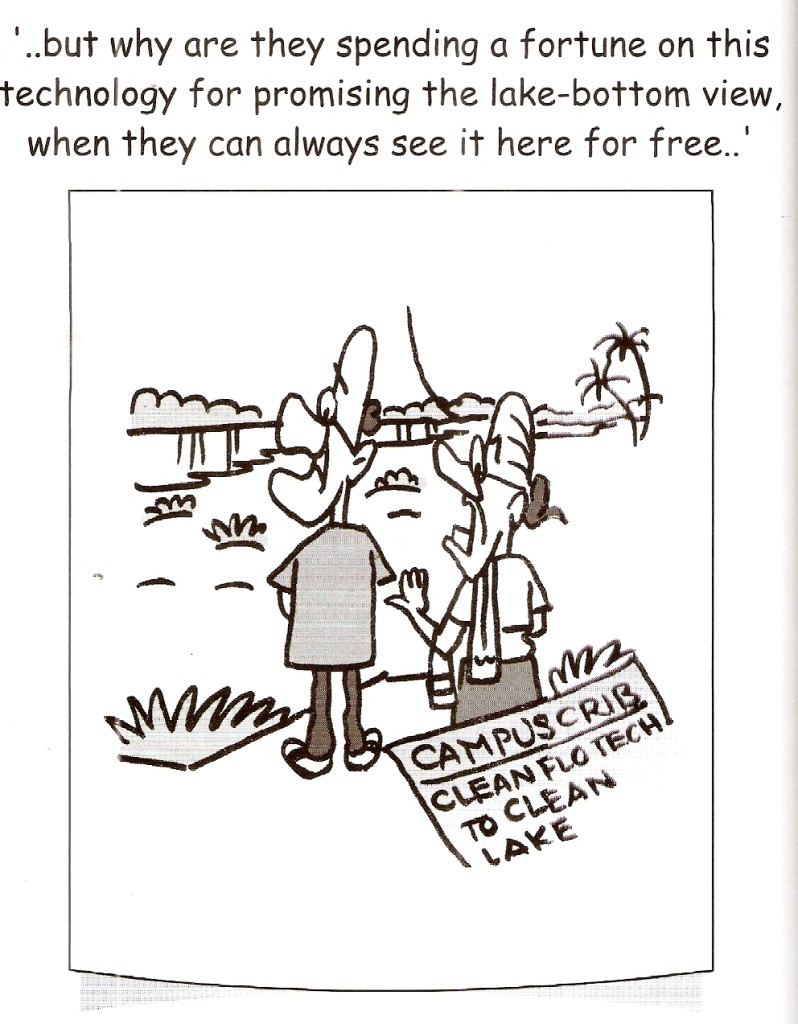

Prof. Inamdar, who has closely monitored the several rejuvenation attempts made for the lake, points out glaring gaps in what he describes as “staggered and primarily aesthetic treatment” of the lake. For instance, when the Class of 1980 realised that the funds they raised couldn’t have made any impact on the lake, the money was reallocated to beautification of the lake road inside IIT-B and the creation of Kshitij – a garden behind the Convocation Hall. But, argues Prof. Inamdar, cosmetic changes around the lakefront are not going to help as they derive their value from the lake. If the lake dries up, the musical fountain, the parks and the promenade will be worthless.

On the subject of water hyacinth, Prof. Inamdar thinks that no matter how many times we clean up the water hyacinth infested areas of the lake, they will return because we are not inhibiting seed germination – the achievement of which will require some methodical planning. The sporadic removal of water hyacinth is like granting temporary relief to the lake or removing a cancerous biomass without curing it of the malady. Getting to the root of the issue (both literally and figuratively), Prof. Inamdar continues, the dense, floating mats of hyacinth are flourishing due to the rampant pollution that creates an ideal habitat for these weeds. This rampant pollution is the result of direct disposal of untreated filth into the lake from the surroundings. These weeds will not go away as long as the lake waters remain polluted. We may recall that Powai Lake which had been created in 1891 to supply drinking water supply for Mumbai was declared unfit for this purpose very early on in its history. In fact, back then, IIT-B was one of the major culprits dumping its untreated sewage in the lake. This was even before the start of quarrying and constructing on and around its catchment area. Since then the water of the lake has been suitable only for non- potable purposes such as gardening and industrial use. To heal this long-suffering lake, we have to focus our resources on eliminating pollution, which is at the root of all its troubles, in a more systematic way.

What is the way out? According to Prof. Inamdar, a more rational approach is to create a buffer zone (or natural strip of vegetation) around the lake that will help to minimise the adverse influence of residential, commercial and industrial pockets that surround it. Without such buffers, Prof. Inamdar maintains, residential and industrial neighbourhoods will continue pouring sediment, fertilisers, pesticides, and many other pollutants into the water body. Another advantage of having buffer zones, he underlines, is that they limit the extent of construction thereby also indirectly controlling soil erosion and sedimentation that result from it.

Another remedial measure that the professor strongly recommends is the setting up of a STP to remove contaminants from sewage at the source of pollution before it is released into the lake. This ensures that only environmentally safe water flows into the lake. Another added benefit of this treated water is that it can augment the scarce natural runoff that reaches the lake these days. In fact, Prof. Inamdar points out that once there used to be a STP on our campus. But this STP, which was located behind H4, was woefully undersized and most of the time not working. Moreover, its location was at a higher elevation than most of the campus due to which much of the sewage rarely reached the plant. The current practice is to redirect the waste water into municipal sewers for disposal elsewhere.

The correct question to ask is not if we are interested in saving the lake but if our endeavours match the scale of the problem? Are we making a sustained effort in the right direction? And, most importantly, are we thinking and working scientifically?

Simple as these solutions may sound, their methodical implementation will take leadership, vision and, as Prof. Inamdar puts it, political will from across the spectrum of stakeholders who stand to benefit from the lake in one way or the other. It also means making a quite a few tough choices and we all will need to sign up for it.

Down to Earth

The moot question is whether Powai basin should have always remained a stretch of wilderness? Probably not. The pressure on land is evident to us. But then should we readily assume that nature is something to exploit whether as a material resource or as a backdrop for our residences? Not necessarily. We must understand that “the earth is not as vast a place as we imagine it to be; nor boundless in its bounty. It has a system based on intricate relationships between the living and the non-living, renewable and non-renewable resources. And only some of the components of the system cannot compensate for the whole. Today’s realisation is to nurture and enhance synergy to the extent that what you consume in your lifetime enhances the quality of your life, but still leaves enough for future generations” (Source of quote: At the Heart of the Campus by Prof. Shyam R. Asolekar and Neha Chaudhari. The article was published in the 2010 anniversary issue of Raintree).

In other words, a sympathetic engagement with nature need not threaten the pace of our development. When we start respecting the delicate web of life that interconnects all of us, the word eternal acquires a whole new layer of meaning beyond its lexical connotation. In nature, eternal is not just everlasting; it is about meeting our own needs without ruining the chances of future generations to do the same. That is how we can all participate in the eternal life of nature.

If we don’t heed now, very soon the lake in our backyard will be gone without even a bog to mark its grave. It is for us to breathe life into this dying lake and return its ecosystem to a more desirable state.

The gift of eternity will follow.

Acknowledgement: Our sincere thanks to Prof. Arun Inamdar for providing the background information for this article.

2 comments

I was sorry to read the slow death of my beloved lake which I saw from 1959 onwards. The lake was pristine then without any trace of pollution and any weed/algae growth. Over the years during my visits to campus I have visually seen continued decline in the quality of lake water, shore line and the growth of aquatic plants in it. Though you site several reasons, predominant among them being the development of residential buildings along the lake, it seems to me IITB bears the main brunt of pollution load on the lake. I could be wrong!!

Even though the current treated sewage water from IITB is directed to the municipal sewage system away from the lake, the past dumping into the lake has added to the present woes of the lake. Stopping the dumping of sewage and other wastes into the lake has to stop ASAP if the lake is to be saved. I am sure everybody knows that but is anybody in the authority ready to do anything.

Several industrial lake water treatment systems are available to slow or curtail the growth of algae and other weeds/[plants in the lake. They may be expensive but could extend the life and beauty of the lake which the following generations of IITians will enjoy and so it may be worth the cost. One of process available is injecting oxygen and/or ozone deep into the waters of the lake to remove oxygen deficiency in the water and thereby kill off the weeds by removing the nutrients – this water remediation technology is available from industrial gas companies such as Praxair and the the powers that be should look into it to get an idea of the costs involved.

It is my earnest hope the serious steps will be taken to restore the Powai lakel!

Oops, a typo: “Though you cite several reasons, predominant among them being the development of residential buildings along… ….”