It is a memory that has faded but keeps coming back occasionally. A giant sea-monster rises from the ocean and leaps for the sailor, who jumps out of its claws in the nick of time and whips out his cutlass and sinks it into the monster. The sound of metal cutting through the cloth-skin of the studio dummy gave away the make-believe, but this final scene from the children’s film ‘Sindbad The Sailor’ has stayed with me since I watched it on a Sunday morning in New Talkies on Hill Road in Bandra, more than half a century ago.

I was reminded of it again as I filled out a frequent flyer application form on an Oman Air flight to enrol as a Sindbad member, since I have become one in the past few months. Sadly, Sindbad now roams the skies not the seas. But there are dangers lurking in the skies today as they were once in the seas.

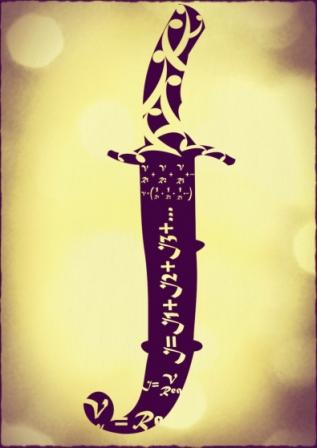

So what happens to IIT professors when they retire? I had vague plans to travel by road and see the country from the comfort my car, as much of it as my pension and the cost of petrol would allow. But stuff happens. So now I am in a place where petrol is cheap, the roads are great and the countryside is spectacular, but they won’t let me drive. Not until I pass their rigorous, multi-stage, driving test after waiting patiently for weeks to geta date. I am now at Dhofar University in Salalah, Oman with a mandate to make their College of Engineering the ‘IIT Bombay of Oman’. It is the first and only university in the Dhofar region, the province that was literally the ‘wild west’ of Oman until recently. The convocation guests come dressed to the hilt, i.e., with a khanjer belted around the waist. But I have not seen a more polite and warm set of VIPs, their khanjers notwithstanding. At a recent conference, a high-ranking but youthful member of the Sultan’s family was the chief guest. When the vice-chancellor completed his welcome address and was returning to his seat, the royal personage stood up in greeting. I wonder who among the present scions of our ‘royal’ families would show such respect to a mere university teacher. I do recall one of them pronouncing summarily that ‘those who can do, those who cannot, teach’.

At a recent conference, a high-ranking but youthful member of the Sultan’s family was the chief guest. When the vice-chancellor completed his welcome address and was returning to his seat, the royal personage stood up in greeting. I wonder who among the present scions of our ‘royal’ families would show such respect to a mere university teacher. I do recall one of them pronouncing summarily that ‘those who can do, those who cannot, teach’.

The students at Dhofar University (DU) are almost all first generation college goers, and for many of them English is their third language, the second being Arabic and the first Jebali. The medium of instruction at DU is English, so the

challenges for the students and the teachers are not unfamiliar to someone coming from India. But what I did not expect was the reception I got from many of them. I had been warned that students will often come to you with all  kinds of unreasonable requests (so what’s new?), please be firm with them. During the first few weeks I had a string of visitors in spotless white dishdasha (ankle-length robe) and kamma (cloth cap with embroidery) greeting me from the door, ‘Salam alaikum – kayfhalik’, and walk up to me and shake my hand. Like I had been warned, I greeted them with cautious warmth, asking them to take a seat and waiting for them to state their ‘problem’. But I soon realised that they were merely coming to greet the new Dean from India and make him feel welcome. Or perhaps to size him up. Many of them have full-time jobs and are taking evening classes to upgrade their diplomas into bachelor’s degrees in Engineering. One day a gentleman, perhaps in his forties, speaking fluent English (so could not be a student), came to see me about a problem with registration. I assumed it was for his daughter, since she was not accompanying him. He corrected me, ‘No, it is for my wife. We have four children and now the youngest one has started school, so she has decided to join college and get a degree in Engineering’. I could have taken my kamma off to him, if I was wearing one. And to top it, he said his job required him to be in Muscat, so

kinds of unreasonable requests (so what’s new?), please be firm with them. During the first few weeks I had a string of visitors in spotless white dishdasha (ankle-length robe) and kamma (cloth cap with embroidery) greeting me from the door, ‘Salam alaikum – kayfhalik’, and walk up to me and shake my hand. Like I had been warned, I greeted them with cautious warmth, asking them to take a seat and waiting for them to state their ‘problem’. But I soon realised that they were merely coming to greet the new Dean from India and make him feel welcome. Or perhaps to size him up. Many of them have full-time jobs and are taking evening classes to upgrade their diplomas into bachelor’s degrees in Engineering. One day a gentleman, perhaps in his forties, speaking fluent English (so could not be a student), came to see me about a problem with registration. I assumed it was for his daughter, since she was not accompanying him. He corrected me, ‘No, it is for my wife. We have four children and now the youngest one has started school, so she has decided to join college and get a degree in Engineering’. I could have taken my kamma off to him, if I was wearing one. And to top it, he said his job required him to be in Muscat, so

his wife was living with his family in Salalah – kamma off to her too, and his supportive extended family.

Salalah is the second largest city in Oman, with a population of under 200,000. In a country with just over four million people, it can count as a city, but to a native of Mumbai it’s more like the population of Powai scattered all over the island of Mumbai. The hills that flank Salalah on one side are called ‘mountains’– the Ghats in miniature really, but the sea that flanks it on the other side is pure azure glass like you will never get to see in Mumbai. The people are friendly and generous like one will sometimes meet in Mumbai, and one can get by with Hindi and English like one can in Mumbai. The temperatures are a shade lower than in Mumbai throughout the year and so is the humidity. Beef is advertised and sold openly – unlike in Mumbai, and Amul butter is widely available –like in Mumbai. I am the only person taking an early morning walk around the campus, no one to disturb my train of thoughts with a greeting or a wave of hand – unlike Mumbai. The roads are neatly paved, no potholes to watch out for – unlike Mumbai. But the few trees on campus are merely ornamental, unlike the thick rainforest that is our campus – in Mumbai.

The hills that flank Salalah on one side are called ‘mountains’ – the Ghats in miniature really, but the sea that flanks it on the other side is pure azure glass like you will never get to see in Mumbai.

I started this column with the thought of writing about life in Salalah and the people and culture of Oman. But I think I will do that another time. There is something else that is distracting me right now.

I suppose you have guessed it – I am missing Amchi Mumbai.