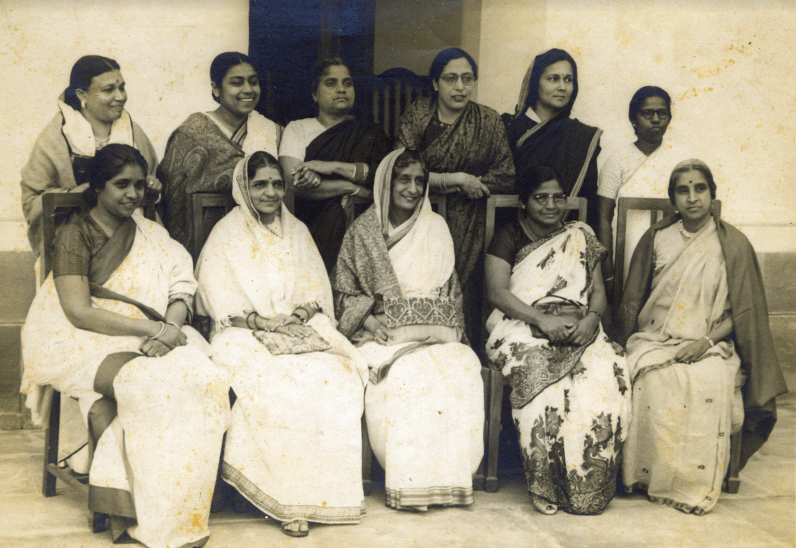

Eleven out of the fifteen women who helped draft the Indian Constitution. The names of the fifteen women in an alphabetical order: Ammu Swaminathan, Annie Mascarene, Begum Aizaz Rasul, Dakshayani Velayudhan, Durgabai Deshmukh, Hansa Jivraj Mehta, Kamla Chaudhary, Leela Roy, Malati Choudhury, Purnima Banerjee, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, Renuka Ray, Sarojini Naidu, Sucheta Kriplani and Vijalakshami Pandit. Image source: link

Briefly, the Constitution is divided into 25 Parts. Today I will refer only to Part III which lists fundamental rights. Most fundamental rights are expressed with reference to the individual and a few to groups but all ultimately afford protection to every individual. Part III contains several Articles (Art. 12-35) but for today, I will refer to only the most basic which underlies all other rights and that is the positive right to one’s identity. Of all the characteristics that make up the identity of an individual, some are of the no choice kind which we are born with and have no hand in determining like gender, race and physical/mental attributes. The other non-physical parts of our identities are accidental and in that sense external such as religion, social or economic — a status which we may have been born into which are changeable but which nevertheless form part of our identities. The right to one’s identity takes within its ambit the rights to equality, not to be discriminated against, the right to live with dignity and to have the freedom to speak, associate with others, move and settle anywhere within India, think freely and profess or not profess any religion. Each of these aspects of one’s identity is expressly protected by the Constitution. Logically and constitutionally, therefore, every person’s identity is necessarily equally important. Nothing offends more than being treated differently on the basis of any aspect of one’s identity for no discernible reason. And yet there can be no doubt that we were and are unjustifiably treated differently by society. Differences were imposed by social and religious traditions which may have had their roots in some historical or other circumstances which are no longer relevant. Yet after 1950 while legally doing away with such inherited differences, the Constitution itself apparently permits differences. Thus while Article 14, mandates that the State shall not deny anyone equality before and protection of the law, the very next two Articles allow the State to make special provisions for women, children, Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Backward classes. Special educational rights are also conferred constitutionally on linguistic and religious minorities. These special provisions are acceptable because they are based on reason, not belief, the reason being that in order to bring about true or substantive as opposed to formal equality, the socially or numerically disadvantaged will have to be given special rights to create what has been called ‘a level playing field’.