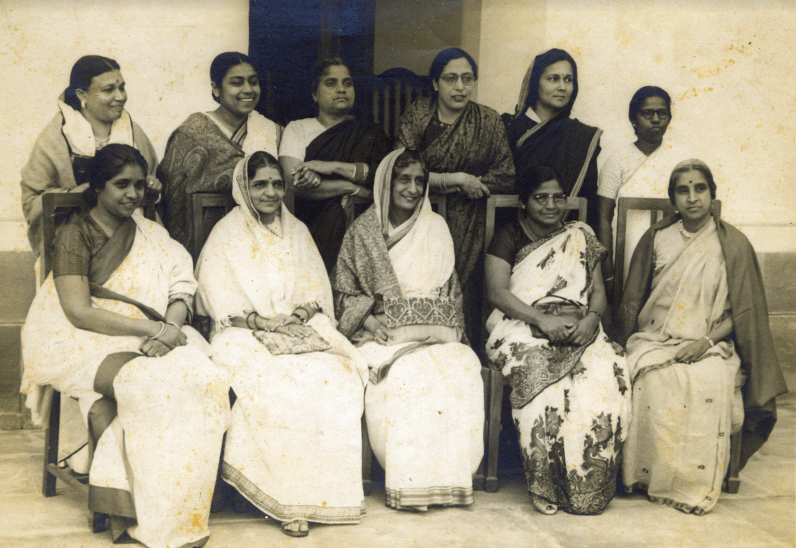

Eleven out of the fifteen women who helped draft the Indian Constitution. The names of the fifteen women in an alphabetical order: Ammu Swaminathan, Annie Mascarene, Begum Aizaz Rasul, Dakshayani Velayudhan, Durgabai Deshmukh, Hansa Jivraj Mehta, Kamla Chaudhary, Leela Roy, Malati Choudhury, Purnima Banerjee, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, Renuka Ray, Sarojini Naidu, Sucheta Kriplani and Vijalakshami Pandit. Image source: link

Briefly, the Constitution is divided into 25 Parts. Today I will refer only to Part III which lists fundamental rights. Most fundamental rights are expressed with reference to the individual and a few to groups but all ultimately afford protection to every individual. Part III contains several Articles (Art. 12-35) but for today, I will refer to only the most basic which underlies all other rights and that is the positive right to one’s identity. Of all the characteristics that make up the identity of an individual, some are of the no choice kind which we are born with and have no hand in determining like gender, race and physical/mental attributes. The other non-physical parts of our identities are accidental and in that sense external such as religion, social or economic — a status which we may have been born into which are changeable but which nevertheless form part of our identities. The right to one’s identity takes within its ambit the rights to equality, not to be discriminated against, the right to live with dignity and to have the freedom to speak, associate with others, move and settle anywhere within India, think freely and profess or not profess any religion. Each of these aspects of one’s identity is expressly protected by the Constitution. Logically and constitutionally, therefore, every person’s identity is necessarily equally important. Nothing offends more than being treated differently on the basis of any aspect of one’s identity for no discernible reason. And yet there can be no doubt that we were and are unjustifiably treated differently by society. Differences were imposed by social and religious traditions which may have had their roots in some historical or other circumstances which are no longer relevant. Yet after 1950 while legally doing away with such inherited differences, the Constitution itself apparently permits differences. Thus while Article 14, mandates that the State shall not deny anyone equality before and protection of the law, the very next two Articles allow the State to make special provisions for women, children, Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Backward classes. Special educational rights are also conferred constitutionally on linguistic and religious minorities. These special provisions are acceptable because they are based on reason, not belief, the reason being that in order to bring about true or substantive as opposed to formal equality, the socially or numerically disadvantaged will have to be given special rights to create what has been called ‘a level playing field’.

Thus while Article 14, mandates that the State shall not deny anyone equality before and protection of the law, the very next two Articles allow the State to make special provisions for women, children, Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Backward classes. Special educational rights are also conferred constitutionally on linguistic and religious minorities. These special provisions are acceptable because they are based on reason, not belief, the reason being that in order to bring about true or substantive as opposed to formal equality, the socially or numerically disadvantaged will have to be given special rights to create what has been called ‘a level playing field’.

I cannot say with any certainty when it started dawning on society that the greatest inequality practised socially, politically and economically within each race, creed, community or caste is on account of gender. However, justified the cause of the subjugation of women in the past, in the present context it is illogical and irrational and the Constitution seeks to right the balance. Nevertheless, society does not generally progress logically and is loth to leave the safe shores of traditional perspectives and consequent customary practices to embark upon a strange new path to what seems an unstructured and alien society of individual freedoms. I use the word ‘generally’ advisedly because the more rational amongst us understood and understand that the new structures for which the Constitution has prepared the blueprint is but a new perspective on age-old truths. Such persons were and are able to bring about changes in the law towards that end.

I cannot say with any certainty when it started dawning on society that the greatest inequality practised socially, politically and economically within each race, creed, community or caste is on account of gender.

To correct the social perspectives various laws intended to protect women have been enacted which touched fringe aspects of the inequality faced by women. In 1961 the Dowry Prohibition Act was enacted; in 1994, The Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Prohibition of Sex Selection) Act, and there were more. On the economic front, the Maternity Benefit Act in 1961 and the Equal Remuneration Act in 1976 are of note. Politically women were sought to be empowered by reserving seats for them in Panchayets and Municiplities by Constitutional amendments in 1992. As far as marriage and divorce are concerned, the closest that Parliament came to affording equality to the sexes was by giving all citizens the option to register their marriages under the Special Marriage Act, 1954 and to be governed by the provisions of that law. But the problems of inequality faced by women in matters governed by their personal laws persisted.

In British India, all laws were divided into criminal, civil and personal. Civil and criminal laws were the subject matter of general legislation and applicable to all, but personal laws covering marriage and divorce, succession and adoption were left to be governed by the personal laws of each religion. The difficulty was that there were different laws within each religion applicable to different sects. In the late 19th Century aspects of personal law were codified for all Christians irrespective of whether they were Protestant, Roman Catholic, etc. Similarly, Muslim sects such as Sunnis, Shias, Bohrasetc were not only governed by their own laws (for example Sunnis follow the triple talaq, Shias do not) but very often followed different territorial laws (e.g. a Muslim in Kerala would follow the local laws of inheritance). It was the British which made the Shariat uniformly applicable to all Muslims sects in India by enacting the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, in 1937. The Shariat, like the earlier Hindu laws, is based on sacred texts and is, by and large, uncodified. However, in 1939 the British enacted the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act, 1939 which gave Muslim women the right to divorce their husbands. Hindu women were left behind as the British had, for the most part, left the personal laws of Hindus untouched.

As far as marriage and divorce are concerned, the closest that Parliament came to affording equality to the sexes was by giving all citizens the option to register their marriages under the Special Marriage Act, 1954 and to be governed by the provisions of that law. But the problems of inequality faced by women in matters governed by their personal laws persisted.

One of the areas in which immediate changes were made in the law post- Independence related to the personal laws governing Hindus. The changes were drastic — particularly in so far as women were concerned. After prolonged debate and in the face of virulent objection which spanned several years, between 1955 -1956, several laws were enacted inter alia granting all Hindu women rights to property, succession, divorce, maintenance and adoption. New laws had to abide by the parameters of the Constitution and old laws contrary to the Constitution were struck down by the judiciary. It was only a beginning but not enough. Traces of old patriarchal discriminatory practices in these laws soon became evident which unfortunately still persist. I will give two examples of this briefly. Section 6 of the Hindu Minority and Guardianship Act, provides “The natural guardians of a Hindu minor, in respect of the minor’s person as well as in respect of the minor’s property …, are—(a) in the case of a boy or an unmarried girl — the father, and after him, the mother…”. The difference is made only on the ground of gender and not because of education or economics or any other reason. Unfortunately in 1999 the judiciary balked at upsetting the patriarchal applecart by striking down the section as violative of equality. The section still stands. Again, when a male Hindu dies his property goes firstly to his children, widow and mother. If all of them are dead- then his properties go to his relatives. When a Hindu woman dies, her property goes firstly to her children and her husband. If neither survives her then all her self-earned properties go to her husband’s relatives. This is surely wholly unconstitutional. But because of the law, when a girl who had been widowed within three months of her marriage, thrown out of the house by her in-laws, took refuge with her parents with whom she lived and earned till her death several years later, died, her earnings were successfully claimed by her sister-in-law’s son and denied to her own mother. The Supreme Court had no option in the face of the law to rule otherwise.

Even these reformative measures are limited to Hindu women. As I said they were done in the 1950s after sustained social and political opposition. I doubt if those changes could have been carried out today with the domination of political over social considerations. Subsequent to the 1950s, only when both have coincided, has change been effected, and today except for Muslims, every religious system has codified personal laws.

One of the areas in which immediate changes were made in the law post- Independence related to the personal laws governing Hindus. The changes were drastic — particularly in so far as women were concerned. After prolonged debate and in the face of virulent objection which spanned several years, between 1955 -1956, several laws were enacted inter alia granting all Hindu women rights to property, succession, divorce, maintenance and adoption.

The shackles of political considerations, fortunately, do not bind the judiciary which was and is left free to strike down or create or mould laws to grant equality to individuals on the basis of the Constitution. It has done so, for example by striking down statutory provisions in the law relating to Christian marriages as unconstitutional, by reading into existing laws a single Muslim woman’s right to adopt and by granting equal maintenance by their husbands to all women irrespective of religion. Recently maintenance was granted to a second “wife” of a Hindu even though bigamy is forbidden under Hindu law. Interestingly the court in granting relief said that even though bigamy was illegal “it cannot be said to be immoral so as to deny even the right of alimony or maintenance to a spouse financially weak and economically dependent”. The reasoning appears to be based more on morality than the logic of the law, but is an example of that innate sense of justice which I have referred to earlier. The judiciary has created laws relating to sexual harassment of women in the workplace by relying on an International Convention ratified by India politically but not implemented legislatively. It has interpreted the law to extend maternity benefits to daily wagers, struck down provisions that debarred women from being employed and upheld special employment provisions for women. All this was done on the basis of the provisions of the Constitution. Courts have had to step in in the absence of any move by Parliament to keep pace with the ever-growing expectations of the citizens. Nevertheless, the laws laid down by courts are limited to the matter in issue before them. A composite comprehensive approach can only be done by Parliament.

The shackles of political considerations, fortunately, do not bind the judiciary which was and is left free to strike down or create or mould laws to grant equality to individuals on the basis of the Constitution.

The codification of Muslim personal laws which had been started by the British became embroiled in political controversy after Independence. The resistance of many Muslims to change in personal laws came from a fear of a loss of identity in the flood-tide of majoritarianism. That fear has become more deep-rooted and widespread as the years have passed. But at the same time, individual Muslim women have become more conscious and vocal of their rights under the Constitution particularly their right to equality within their community. Take for example divorce. Every Muslim woman can divorce her husband on specified grounds through the court under the Muslim Marriages Dissolution Act, 1939. A Sunni Muslim husband can divorce his wife on any grounds without going to court merely by repeating the word ‘talaq’ thrice. It was only in 2002 that the Supreme Court in Shamim Ara approved Justice Baharul Islam’s opinion expressed as early as 1981(i) that “talaq” must be for a reasonable cause; and (ii) that it must be preceded by an attempt of reconciliation between the husband and the wife by two arbiters, one chosen by the wife from her family and the other by the husband from his. If their attempts fail, “talaq” may be effected. It is doubtful whether the members of the community are at all aware of this or whether this has been enforced at the ground level. It would have been more effective with a legislative endorsement of this judicially authoritative view of the applicable law. This was not done till the practice of triple talaq itself was set aside last year in 2017 by the Supreme Court in ShayaraBano‘s case on the ground that it violated the Constitution. I do not think that those who spoke in favour of triple talaq could seriously argue that it was an equitable provision or in keeping with the equality clauses in the Constitution.

The codification of Muslim personal laws which had been started by the British became embroiled in political controversy after Independence. The resistance of many Muslims to change in personal laws came from a fear of a loss of identity in the flood-tide of majoritarianism. That fear has become more deep-rooted and widespread as the years have passed. But at the same time, individual Muslim women have become more conscious and vocal of their rights under the Constitution particularly their right to equality within their community.

The ground which was pressed by the status-quoists was that personal laws, including marriage and divorce, formed an intrinsic part of the Muslim religion and was protected by the fundamental right to freedom of religion under Article 25. The Supreme Court held rites of marriage and divorce do not form an integral part of any religion. Besides, the fundamental right to freedom of religion or conscience under Article 25 is not absolute in the sense that the Article in terms allows the State to modify personal laws in the interest of public order, morality and health and for providing social welfare and reform. That one’s religious beliefs forms part of one’s sense of self cannot be gainsaid but what of that aspect of one’s identity which is even more deep- rooted–that of gender?

Till very recently, all the reformative measures (whether statutory or judicial) to protect and further individual rights, had concentrated on the gender inequality between women and men. Those that fell in neither group were at best ignored or, at worst, persecuted as being socially aberrant completely overlooking the biological nature of their difference. One of the statutory provisions which was used for such persecution was section 377 of the Penal Code 1890, which provides for the punishment of voluntary ‘carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman or animal’. If something is the order of nature, can society predicate otherwise? A sexual preference is determined by biology. Society follows nature by recognizing its laws; nature cannot be expected to follow society’s laws. If gender is basic to a person’s identity, which even the Supreme Court has held it is, then it follows that sexual preference is the right of every individual. Depending on one’s biological set up, one’s preference of members of one’s own sex is as ‘natural’ as the preference of members of the opposite sex. Yet in 2014 the Supreme Court in Suresh Kumar Koushal v. Naz Foundation refused this right to the former on the ground that “a miniscule fraction of the country’s population constitutes lesbians, gays, bisexuals or transgenders and in last more than 150 years less than 200 persons have been prosecuted (as per the reported orders) for committing offence under Section 377 IPC and this cannot be made sound basis for declaring that section ultra vires the provisions of Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution”.The judgment offended the more rational amongst us as well as those who were well aware that the Constitution expressly protects the individual and that numbers are irrelevant. Fortunately, within a few years the Supreme Court corrected its course and reaffirmed “Gender identity is one of the most fundamental aspects of life which refers to a person’s intrinsic sense of being male, female or transgender or transsexual person”. It was also said “The discrimination on the ground of “sex” under Articles 15 and 16, … includes discrimination on the ground of gender identity. The expression “sex” used in Articles 15 and 16 is not just limited to the biological sex of male or female, but intended to include people who consider themselves to be neither male nor female”. The explicit overruling of the earlier decision of the Supreme Court in Suresh Kumar Koushal v. Naz Foundation is now only a formality.

Till very recently, all the reformative measures (whether statutory or judicial) to protect and further individual rights, had concentrated on the gender inequality between women and men. Those that fell in neither group were at best ignored or, at worst, persecuted as being socially aberrant completely overlooking the biological nature of their difference.

The recognition of the different genders by the courts as not only part of every individual’s identity and therefore equally entitled to all the freedoms and rights provided by the provisions of the constitution is a major correction of the course by the judiciary. This recognition of every aspect of one’s gender identity must be followed by Parliament in order to bring about comprehensive implementable reform. Whether the reforms will be effective however will depend to a large extent upon the Executive and above all on the individuals themselves constituting society to make them effective.

However, in my opinion, the final correction will come when an individual’s own perception or society’s perception of an individual’s identity is not limited to that one characteristic of gender and gender becomes important only when it is relevant. I agree that, at least on the temporal level, gender may be basic to our self -perception. But it will be a tragedy if in recognizing one’s own potential or the potential of others– every other aspect of one’s identity is ignored and one perceives oneself and sees others only through the prism of gender.