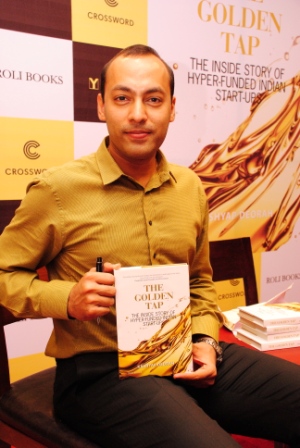

‘The Internet Changes Everything’ has been extracted from Part 1: The Internet Wave (1994–2002) of the book ©’The Golden Tap: The Inside Story of Hyper Funded Indian Startups’ by Kashyap Deorah.

Heady Days at Amazon

Until mid-1998, Amazon had one website, one category, and one giant 100,000 sqft warehouse in South Seattle employing many hundreds of employees. This was sufficient to power 4x a year business growth but Bezos was hungry for more. His motto became ‘Get Big Fast’ and he pasted it on the walls at Amazon. Brick-and-mortar retailers like Barnes & Noble and Walmart had started coming after Amazon. It was time for Bezos to demonstrate his Wall Street savvy as much as his flamboyance as an entrepreneur. He borrowed nearly $2.2 billion in loans over two years to fund the expansion to five additional giant warehouses. He spent some of that cash to buy minority stakes in e-commerce companies in other categories: Exchange.com, Drugstore.com, Pets.com, Gear.com, Wineshopper.com, Greenlight.com, HomeGrocer.com, and Kozmo.com.

While Bezos created an organizational cult around being customer centric and not competitor-centric, he was aware of looming competition and hated to lose. The mainstream sentiment at the time was that Bezos had woken sleeping giants and that the brick-and-mortar retailers with their large operations, balance sheets, product depth and margins would walk all over Amazon with their new online businesses. But Bezos was more worried about the start-up founded in 1995 as AuctionWeb. It was now called Ebay and was about to go public in September 1998. The beauty of the Ebay model over Amazon was that they had no warehouses, had all categories at once, allowed the buyer/seller to arrive at the perfect price through an online auctioning process rather than determining the right fixed price themselves, and made money from every product listed on the site and a commission on every sale. Bezos was a believer in the power of the Internet and how brick-and-mortar players would not be able to compete in that arena. Ebay was a competitor on his turf. Ebay’s IPO was a roaring success. Shares floated with a target price of $18, opened over $53 and closed the day over $47. In 1998, Ebay’s revenue was $48 million, but Bezos knew that the number to compare was the Gross Merchandize Value calculated as total invoiced sales. Ebay was at $746 million and ahead of Amazon at $610 million. While Amazon made a loss of $125 million in1998 (-20 per cent), Ebay made a profit of nearly $40 million. It was hard to ignore an e-commerce company whose margins of 85 per cent looked like that of Microsoft, while Amazon was a loss making company whose margins might eventually look like Walmart’s.

After becoming a part of Amazon, the Junglee team first started working on ‘Shop the Web’, which let shoppers look at product prices on other websites and click-through to leave Amazon.com and buy it elsewhere. After that fizzled out, they worked on Amazon Auctions, which attempted to become an alternative to an Ebay-like marketplace for small businesses to sell to Amazon customers. Amazon learned the concept of marketplace ‘network effects’ the hard way. Buyers were new to the concept of bidding on Amazon.com and wanted a critical mass of sellers before they would get comfortable with the idea. Sellers would participate only if there were a critical mass of buyers bidding.

Between 1998-2000, in an 18 month run that you had to see for yourself, the world of technology became pop culture. What was previously the domain of software geeks in Silicon Valley had now become a topic of discussion in every party, business, household, and college campus.

Amazon Auctions was unable to build a network to compete with Ebay. Amazon Auctions evolved into Zshops, a fixed price marketplace where small businesses could list their inventory on Amazon.com with a fixed price of their choosing, alongside Amazon’s own price for the same product and more in tune with the customer’s expectation on Amazon.com. It was a bumpy start and highly controversial within the company. However, it stood the test of time. Though Amazon does not give a break up in their financials any more, 16 years later in 2015, it was estimated that somewhere between one-fourth to one-third of Amazon’s transactions came from the Amazon Sellers marketplace. The Junglee team was at the core of starting this platform, and guess who they finally hired to be part of the initial team of Zshops in February 1999? My friendly neighbour Amit Agarwal. While the Junglee team left Amazon in 2000, at the time of writing this book, Amit had stuck with Amazon for over 16 years.

Things came a full circle when 13 years later, in February 2012, Amit led Amazon’s entry into India and his first consumer-facing move was the launch of a comparison shopping website called junglee.com. After a year of learning what Indians wanted to buy and at what price, in June 2013, Amit launched Amazon.in.

The IIT Bombay Start-up

After the Junglee acquisition in 1998, Rakesh Mathur had started frequenting his alma mater IIT Bombay. IIT held a special place in his life since he grew up on campus. Rakesh’s father was a prominent professor at IIT Bombay from 1969 to 1997. He founded IIT Bombay’s Student Gymkhana where, as President, he hired most of the sports coaches and commissioned the creation of the sports facilities and the Student Activity Center. Between1996-2000 at IIT Bombay, I was coached by the football, cricket, tennis, athletics and basketball coaches, allof whom were originally hired by him.

By now, IIT was probably the only place in the world where Rakesh was introduced as the son of Professor Mathur first, and as a successful entrepreneur second. During his visit in late 1998, soon after the Junglee acquisition, he spoke at an entrepreneurship workshop organized by a third year student Anshuman Bapna. During the speech, he narrated stories about how Stanford University was a bedrock for the innovation in Silicon Valley, which in turn was a beacon for technology innovation in the world. HP, Sun, Yahoo!, Google and his own company Junglee, were born inside the university campus. He shared his commitment towards his vision to create a similar foundation at IIT Bombay. To put his money where his mouth was, he declared to the audience at the Lecture Theatre that he would invest a crore (about $250,000 at the time) in a start-up idea that convinced him about their ‘value model, passion and ability to execute’.

Bapna’s friend Mayank Jain, popularly known as Cartoon on campus, was in the audience. He took the challenge quite seriously. Cartoon and I had been part of the founding team of the first technology festival of IITBombay, Techfest that took place in January 1998. After the event’s success, the student duo who co-headed the first Techfest, showed tremendous commitment and vision towards making it an annual festival. They partnered with professors and administrators who shared their vision, wrote a constitution for the event’s organization, built standing relationships with sponsors and other engineering colleges, and created a healthy pipeline of esteemed speakers. The quality of leadership was stellar and inspired a wave of student organizations spawning on campus, all using the Techfest playbook.

Arguably, the 27-year-old cultural festival Mood Indigo started borrowing a page or two from the Techfest playbook. While I went on to lead the second version of Techfest to be held in January 1999, Cartoon organized a job fair called Crossroads, and Bapna created a series of entrepreneurship talks and workshops called Enterprise, which evolved to become IIT Bombay’s Entrepreneurship Cell. While Silicon Valley and the technology world were going crazy from 1998-2000 with starting companies, students at IIT Bombay were going crazy starting programs and festivals on campus.

In the first half of 1999, Bapna, Cartoon and I decided to start a company together and spent the better part of our third year coming up with a business idea to pitch to Rakesh. In the third year of IIT, students pick a topic and write a report on it, then present it to a committee as a seminar. I chose to do a seminar on Internet businesses under the guidance of Professor Deepak Phatak. The report attempted to articulate how the Internet had given birth to new business models that could not exist before, and provided a framework around how they could be categorized. It had three sections: business to consumer (B2C), business to business (B2B) and infrastructure. All of this helped organize my thoughts and research around the business we could start.

Bapna’s approach was driven by his activities with entrepreneurship cell. He was dreaming up the best ways to expose students of IIT to entrepreneurship. Cartoon’s approach was driven by hours spent on the Internet looking at new businesses that were gaining traction as well as making money. We met often and brainstormed around the Lecture Theatre and coffee shack. We shortlisted a dozen ideas, ranked the top three, and then took the plunge with one. We saw the Internet as a medium that brings meritocracy and level voice to the world. We wanted to unleash it in the space of creative ideas. RightHalf.com,* a marketplace for creative ideas [*Creating an electronic book reader came a close second. We pitched that to Rakesh as well. He turned it down because it involved ‘atoms’ (physical world) in addition to‘electrons’ (virtual world).]. All the world for half a thought. If you had an original idea that could be expressed digitally, go post it on RightHalf.com. Users could rate it, review it, comment on it, add to it, traverse from one idea you liked to other similar ones, follow a person whose ideas they loved, and so on. We pitched it to Rakesh over the phone. One call led to the next, the next one led to three more. Rakesh said, value model – check, passion – check, ability to execute – question mark. We (mainly Cartoon) worked hard to code up a demo. In December 1999, Rakesh decided to visit campus again.

Rakesh had all ducks in a row. He arranged a ‘pitch meeting’ at the Ambassador Hotel at Churchgate in South Mumbai. Rakesh’s classmate and Infosys co-founder Nandan Nilekani was invited. My guide and IIT’s de facto fundraiser professor Phatak was invited. Rakesh and the three founders of RightHalf.com drove from Powai to Churchgate in my little blue Hyundai Santro that I had on campus. Oddly enough, the New York Times journalist Celia Dugger who wanted to interview Rakesh had tagged along with him through the day, taking pictures and making copious notes while being Rakesh’s shadow. When Rakesh asked us if we would be fine with her accompanying us, we three founders simply stared at each other and shrugged our shoulders. It was unsettling to see an international journalist clicking pictures of every key moment in that day, though I would be lying if I said we did not enjoy the attention. It was the 1999 version of reality TV with live cameras pointing at us while making a pitch that would change our lives, regardless of the outcome. We would be in the New York Times, either as the guys who were able to raise the money or the guys who failed to do so.

As we entered the elevator to get to the rooftop of Ambassador Hotel, Rakesh joked if we were ready for our ‘elevator pitch’. This was the first time we had heard the phrase. During the Internet boom, it was a popular phrase for a short persuasive pitch that an entrepreneur should be prepared to make to an investor in the event of a chance meeting in an elevator. All of us settled in the conference room overlooking the Arabian Sea. They heard the pitch. Prof. Phatak summarized the outcome. Rakesh would invest $250,000 and join the company board, Rakesh would pledge his shares to the IIT Bombay Heritage Fund, IIT Bombay would set up a business incubator funded by Nandan and under the guidance of Prof. Phatak, RightHalf.com would be the ‘pilot’ of the incubator. We shook hands. Bapna, Cartoon and I left the room and watched waves crashing into the walls of the Marine Driveside walk while eating baked, spiced nuts and absorbing the gravity of what had just happened.

RightHalf.com launched its Beta website. The word was spreading around campus and amongst alumni worldwide. Content had started trickling in. People were posting jokes, business plans, conspiracy theories, guitar riffs, photos, chapters of books, riddles, call to action on causes, and lots of random thoughts that had crossed their minds at the moment they were staring at our website. The team was enthralled. We had tens of thousands of users checking us out. We were working on upgrading the server software to be able to handle the inevitable hundred thousand users that we would reach in a month. The growing team had always kept us on the move. We had moved from our two workstations in a lab to a faculty room in the Math department. The late nights and never-ending playlists were not going well with other faculty members whom we shared the hall with. This accelerated our move to the third floor of the Physics department where IIT Bombay’s business incubator had set up a new office. And now we were about to move out soon. Outside the campus this time. Out in the big bad world. In the up and coming neighbourhood of Hiranandani Gardens in Powai, a few kilometres outside campus.

Pop Goes the Bubble

To describe what happened on Wall Street and in Silicon Valley, I quote the Nobel Prize Laureate Professor Robert Shiller: ‘Irrational exuberance* is the psychological basis of a speculative bubble [*A phrase coined by Alan Greenspan, Chairman of the US Federal Reserve during the dot-com boom and bust.]. I define a speculative bubble as a situation in which news of price increases spurs investor enthusiasm, which spreads by psychological contagion from person to person, in the process amplifying stories that might justify the price increases and bringing in a larger and larger class of investors, who, despite doubts about the real value of an investment, are drawn to it partly through envy of others’ successes and partly through a gambler’s excitement.’ The slide begun on 10 March 2000. Prof Shiller’s book was published on 15 March 2000. The release of his book, Irrational Exuberance, could not have been timed more perfectly.

We were still students at the time. Our team consisted mostly of classmates, all on the verge of graduation. Two of them were headed to Stanford, one to Princeton, and only two were likely to continue beyond the summer because they had another year left at IIT. We would have to learn to hire professionals. While we were getting done with the final semester of our four years at IIT, Nasdaq was getting done with the final spike of the four year period of speculation around tech stocks. Nasdaq crossed the 5,000 mark to hit an all time high peaking at 5,132.52 in the afternoon of 10 March 2000 before closing at 5,048.62, and then the slide began. In the trading week of 10-14 April 2000, Nasdaq shed more than 1,100 points, its biggest one week loss in history. The writing was on the wall. The speculative rise of tech stocks was a bubble. It had burst. 14 April 2000 was now called Black Friday. Just as it would take us a few months to absorb all the implications of graduating, it would take us a few months to absorb all the implications of the dot-com bubble burst.

Rakesh introduced us to his co-founders at Junglee: Ashish, Venky, and Anand. After leaving Amazon, Venky and Anand had started an early stage fund called Cambrian Ventures, focusing on ideas with deep Ph.D. level technology. Rakesh had started a fund called Skyblaze Ventures and Ashish used to invest with Skyblaze. RightHalf.com was one of the first investments of Skyblaze. When we met Ashish at a hotel in New Delhi, we were struck by his passion and humility. From the restaurant where we met to the lounge where we continued the conversation, he enthusiastically hopped ahead of us and held every door for us on the way. With every door that he held for us, it opened another door in my head. First door: I am feeling embarrassed. Why? Second door: the default code in my head says the lesser or younger person opens the door for the more successful or older person. Why? Third door: should I race ahead of him and hold this door? Is that what he wants me to do? Would I offend him if I do? Can we revert to default code of conduct among peers, ‘every man for himself ’? Fourth door: thank heavens Cartoon spoke ‘Ashish, you don’t have to hold the door for us. It is a bit embarrassing’. Phew. Fifth door: There, he did it again. And to top it off, he apologized for it. Said, he forgot. It’s a reflex action. Said he is sorry if he made us uncomfortable! There were no more doors. Well just the one that his card could unlock. Non controversial.

Ashish was always passionate about India. He seemed committed to eventually moving back there to contribute as an entrepreneur and investor. He had co-founded a Silicon Valley headquartered services company called Haathi.com with a large engineering set up in India. He was soft on the people and hard on the issues. He gave us some of the most critical feedback that we needed to hear. He told us why we needed to focus on revenue and profits, and why eyeballs alone do not make a business. In a surprisingly non-threatening way, he convinced us about the reality that had not sunk in until then. That we were no more a special breed of people in a protected environment. We were no more a set of kids executing the script of a larger than life angel investor. We were out in the big bad world where yesterday’s headlines did not matter. We were only as good as our last innings. We had to sink or swim. We had to find it in ourselves to build a sustainable business or die. Ashish became our mentor for the rest of our careers.

A new problem had now started coming to fore at RightHalf.com. We operated by consensus. Three equal founders made decisions equally. All three on the board of directors. Like friends in IIT, it was important that we all agreed with something, or at least get comfortable with it, before we did it. One for all, all for one. The company had three founders but no CEO. I had broached the topic on a few occasions when things were going well, and then on occasions when things were not going well. Our inability to agree about whether we needed a CEO reflected that there was no one person that had our consensus for being first amongst equals. In times of change and adversity, we had to make some tough decisions and our style of operation hampered that. Bapna was the senior most amongst us. Cartoon and I had the strongest opinions, and Bapna would usually play moderator, striking a compromise. One of the strong opinions that Cartoon and I differed on was that I thought we needed a CEO and Cartoon thought we did not. We agreed that Bapna would be CEO. Rakesh’s words used to ring in my head: ‘You cannot lead unless you can follow’.

But it was turning out to be easier said than done. Over the next few months, we squabbled like school kids. I started throwing tantrums, unable to ‘disagree and commit’ like Rakesh had taught us to* [*Rakesh learnt this, and other tenets he taught us, from Jeff Bezos at Amazon. ‘Have Backbone; Disagree and Commit’ was one of the fourteen leadership principles at Amazon. ‘Leaders are obligated to respectfully challenge decisions when they disagree, even when doing so is uncomfortable or exhausting. Leaders have conviction and are tenacious. They do not compromise for the sake of social cohesion. Once a decision is determined, they commit wholly’.] At one point, I resigned from the board of RightHalf. Cartoon and Bapna said they would be fine with it as long as I ran it by Rakesh. Rakesh said I was free to do what I wanted to do, but it would not hold me in good stead with him or any future investor that I was walking away from my commitment. We still had a reasonable amount of money left in the bank. It was the first time that I saw him get angry. At the end of the call, he made a decision: ‘Take some time off, get that fucking drive back, and come back and lead.’ He communicated his decision back to the other two. I returned as CEO, but things were never the same again between the three founders.

Towards the end of 2000, our team settled in our new office outside the campus. For my graduation ceremony, I had walked from RightHalf ’s office at the incubator on campus to the convocation hall. The feeling of being out in the big bad world had not yet sunk in after graduation. The physical move out of our cocoon and into the depths of Hiranandani Gardens had finally woken me up to that reality. RightHalf.com was growing in traffic but with no business model. Rakesh called us to the US for an off-site. He had moved from the Bay Area to Seattle. Apparently, Bezos was not taking any chances with having to pay taxes for orders from California. The new consumer technology that was growing like wild fire was music-sharing service Napster.

Peer-to-peer technologies set a new benchmark for user growth. Rakesh’s view was that if we wanted to stick with the traffic growth game, our new benchmark would have to be Napster. If not, we should focus on making revenues rather than chasing user growth. We appreciated the clarity. Our traffic trends were nowhere near that of Napster. It was decided. We would become a provider of ‘bulletin board and community technologies’* for other consumer websites [*The phrases ‘blogging’ and ‘social networking’ were not mainstream yet. It would be four more years before they did.]. We would re-package our existing platform to offer software as a service to larger consumer-facing websites, and use our India set-up as a competitive advantage.

While Rakesh got us focused on a clear business plan, in his mind that was plan B. His new company PurpleYogi was going through a similar transformation, from a B2C company to a B2B company. They were in the process of setting up a new India office with senior management. The plan A brewing in his head was to merge our team with his new India team. That could be a win-win for both companies. As young entrepreneurs barely out of college, selling our first company to a high-profile Silicon Valley based start-up was hardly an outcome to be ashamed about. For PurpleYogi setting up shop in India, seeding it with a team of IITians working on similar Internet technologies, was worth a reasonable chunk of stock. Since he had conflict of interest, he seeded the idea of PurpleYogi acquiring RightHalf to both companies and then left it to PurpleYogi’s VP of Engineering to negotiate directly with me. We negotiated. We had a deal. The team moved to PurpleYogi’s new offices in Bangalore. Five years later, one of the RightHalf employees would go on to win ‘employee of the year’ at PurpleYogi, now called Stratify, for three years in a row.

We were blurring the boundaries of geography, living in the new world order created by the Internet. The world had not come to understand the Internet, while we were writing the rules for it, as it were.

In the Bible, Jesus says in the Sermon on the Mount: ‘All things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them’. While the author of the book wanted people to program their brains to do to others what they would like others to do to them, I have concluded that the brain’s default programming is its corollary. People do to others what others have done to them. I learned from the Junglee founders that if I could only apply that to my life by doing to others all the good things that others have done to me, the world would be a better place. Rakesh was being our Taira-san by funding us. Just as Taira-san emphasized the importance of founder chemistry to the Junglee founders, Rakesh did the same to us. Just as Bezos taught Rakesh to always hire people better than him, Rakesh emphasized the same to us. Just as freshly graduating students from Stanford were given a shot at building Junglee, the Junglee founders would do the same to freshly graduating students from IIT Bombay. Just as Prof. Ullman encouraged his students to start companies, Prof. Phatak would do the same to us. Probably for the same reason though in an entirely different context, just as Junglee had been merged with a new initiative by Amazon, RightHalf would merge with a new initiative of PurpleYogi.

We had barely crossed our 20th birthdays and had the press regularly lined up outside our offices smelling of filthy sleeping bags. We were managing more money in the bank than our parents were in their personal or professional bank accounts. We were blazing the trail for IIT Bombay to become another Stanford University and Powai to become another Silicon Valley. We were building a global company out of India when the only tech business that India was known for was IT services and outsourcing. We had raised equity capital when there were no venture capitalists investing in early stage tech start-ups in India. We were starting a movement by staying back in India when everyone in our batch left for the US, and those who stayed were the ones who could not go. We were blurring the boundaries of geography, living in the new world order created by the Internet. The world had not come to understand the Internet, while we were writing the rules for it, as it were. At least, that was our story at the time.

It played out slightly differently. Year 2000 was a roller coaster year for Silicon Valley, Wall Street, IIT Bombay, Amazon, Junglee and RightHalf.com founders. We started the year with our classmates working for us on a stipend and kept moving offices within campus. By the middle of the year, most of them graduated and headed to the US for further studies. Our fanatical focus at the start of the year was to get a million monthly users to our site. By the middle of the year, we were wondering how we could make a million dollars in revenue instead. We ended the year with professionals hired from the open market, offices outside campus and a face saving acquisition by a Silicon Valley company.

The fuel that had powered the jets to defy gravity had run out. Gravity had kicked in and the free fall had begun. The higher you were, the mightier you fell. Gravity had always been there. It was the jetpacks that created the illusion of anti-gravity. The excesses of the good times had to be accounted for. The jetpacks had to be returned in good condition and the amounts due had to be settled.

Junglee founders started the year with the Amazon stock over $100 and ended the year at the stock being under $15. They were counting their blessings for what they had sold. Amazon lost over $1 billion in the business, piled up debt of over $2 billion, and lost over $18 billion in marketcap as the slide continued. Bezos was under severe competitive threats and dealing with criticism inside and outside the company about the maverick way in which he had built the company. Amazon was dealing with churn in leadership. All their B2C dot-com investments had perished in the bubble and the company did not have the bandwidth to deal with it.

IIT Bombay started the year with a record funding from IIT alumni. By the middle of the year, the institute was dealing with a myriad of controversies around students losing focus due to activities and events on campus. The motives of alumni funding new buildings and departments to be named after them was under question. Professors were taking exception to students misusing the name of IIT to get free press and monetary gains for themselves and their companies. Formation of new departments was seen as taking away faculty and resources from existing ones. The year ended with rules written and lines drawn. All initiatives that had cropped up uncontrolled now needed to get in line and follow rules.

The fuel that had powered the jets to defy gravity had run out. Gravity had kicked in and the free fall had begun. The higher you were, the mightier you fell. Gravity had always been there. It was the jetpacks that created the illusion of anti-gravity. The excesses of the good times had to be accounted for. The jetpacks had to be returned in good condition and the amounts due had to be settled. The brain that switched off fear to survive the social psyche of the bubble had now switched on the fear to high levels of morbidity. The cops were out to punish the perpetrators and they were having a field day.

[The book was first published by The Lotus Collection, an imprint of Roli Books Pvt.Ltd , India, in 2015. It is available for purchase on Amazon.in as a Print and Kindle edition. The Fundamatics team has reproduced the piece ‘The Internet Changes Everything’ in two installments. The first part is available here.]