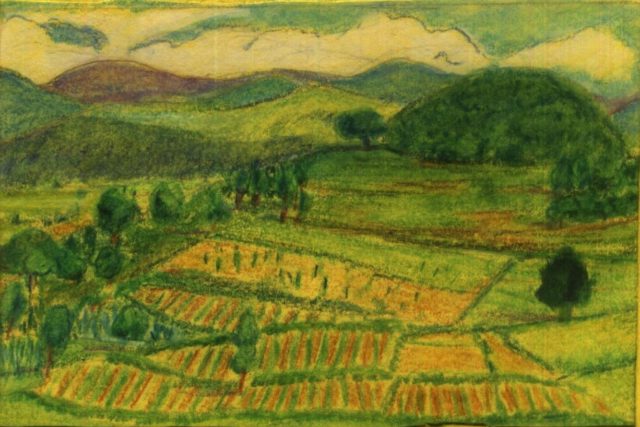

Illustration by Pradnya J

To the temple on the island

Was always late

Dependent as she was

On the whims of the boatman

Sunderarajan Venkatavaradan (SV, H7, 820448) is an ex-IITian. He earned a B.Tech in Electrical Engineering ('86). He writes at https://medium.com/dil-se

Illustration by Pradnya J

To the temple on the island

Was always late

Dependent as she was

On the whims of the boatman

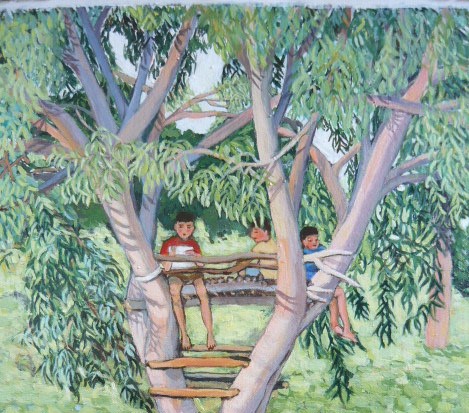

Illustration by Harshita Bandodkar

Pandora’s box is open

And the -ism’s are flying about

Nationalism has bitten her quite badly

Her friend has been stung by Doubt.

The -ism’s are creating schisms

Between him and me and you

Is there any remedy for this?

What is the best thing to do?

Try and get stung by Kindness

And we may well be able to cope

Open the box again quickly

And let out poor, trapped, Hope.

Artwork by Rajat Patle

Illustration by Nilapratim Sengupta

The universe is made up of not only atoms but also stories. So when I was asked to write for the Climate Change issue of Fundamatics, I knew I would have to write our story, about our small bit of the universe, which would then become a small cog in our small bit of the universe.

Some years ago, we had a visitor, who asked us how we had managed to acquire Forest land. Had we just squatted on it? Or had we managed to acquire a patta of some sort?

It took us a while to convince him that the forest came after we did. And we realised that we ourselves hadn’t seen the wood for the trees.

When Sonati and I moved here 20 years ago with a two-and-a-half-year-old Badri Baba, it was to grow our children up away from the city.

The land was chosen (by both of us independently) almost whimsically: “What a lovely view!”

The land was on a hill, grazed to death; and all the trees hacked for firewood. Where would the water come from? Didn’t daunt us.

Recklessnes? Youthful energy? Perhaps both; perhaps.

There’s a divinity that shapes our ends,

Rough-hew them how we will.

Otherwise, given the difficulties with water, the barrenness, the rockiness, no-one may have bought this piece of land.

The House in 2000

And since we did, the land has now become green, and treed-up. Various birds have moved in which we never saw here earlier.

The House in 2020

We have seen slender lorises (we hear them oftener than we see them), and a family of mongooses. (And Varun Baba, too moved in!)

Various neighbours steal various things: Jackfruit, Guavas (though of late we have had a relentless stream of kids who actually come and ask for Guavas. The squirrels don’t ask), Firewood, Timber wood, the land itself by pushing boundaries.

I seem to have moved to the end of the story so far, skipping over various intermediate stories. But that is just like a story; it takes on a life of its own.

Much like our land, which too seems to have a mind of its own.

We tried so many things: We grew rice (rainfed), ragi (rainfed), dal (rainfed), til for oil (rainfed). The trouble was that our neighbours had started growing cash crops (tapioca: Salem is the tapioca capital of the world). The upshot: All the rats grazed on our tastier crops, and would leave the husk for us to estimate how much they had eaten. To add insult to injury, after we harvested our crops, the rats would start eating tapioca for want of anything else: And our neighbours would say, “Saar, your rats have come to our fields”

So…

When the rats were consuming 80% of our crop before we could harvest it.

We had to give up growing rat food.

Then we planted out trees: fruit trees, flowering trees, timber trees; and of course, the native trees which grew back from hacked stumps, since we stopped people grazing and collecting firewood on our land.

Our trees were also all rainfed: we had to plant at the right time and pray. We used to get two monsoons (July to September is the short-rainy season, October-November is the long-rainy season) and also some January rains and some April rains, so we didn’t have to pray too much.

In the last four years, the rains have been pathetic. Not a drop of rain from end of November to the following July. And the monsoons too giving half our normal rainfall.

So we can say categorically that no tree amongst the thousands of our standing trees has been planted between 2015 to 2019. Not one of those survived.

To take that a bit further, we need to say that growing trees needs help from the universe. Had we arrived here 15 years later than we did, we may have thought that this hillside was a dead loss. And a small bit of the universe would have stayed barren.

This may seem anecdotal evidence for climate change. But now there are plenty of such stories, kilo-anecdotes if you will. We need to make the connections and alter our behaviour. After all, if a Pangolin’s sneeze can grind the whole (human) world to a halt, the universe is capable of taking corrective action with or without our help. Perhaps one of our favourite poems from Wendell Berry will sum it up:

Geese appear high over us,

pass, and the sky closes. Abandon,

as in love or sleep, holds

them to their way, clear

in the ancient faith: what we need

is here. And we pray, not

for new earth or heaven, but to be

quiet in heart, and in eye,

clear. What we need is here.

Illustration by Nilapratim Sengupta

When I am out

Pitting

And planting trees

I rue the time

Away from my desk:

I could have been

Writing poetry

I think

When I am

At my desk

Writing

I rue the time

Away from the pits:

I could have been planting trees

I think

But then it strikes me

That in the battle against

Climate Change

Both trees and poetry

Are necessary

Who knows whether

My hundredth poem or

My hundredth tree

Will make me

The hundredth monkey

Illustration by Nilapratim Sengupta

We (Sunder and Sonati) have spent much of the last twenty years in growing trees and our children, here in Thekambattu. No time for anything much else than housework, land work, the kids and visitors. Now, with the boys grown up, and the trees to some extent, there was time for poetry.

The poetry started as a response to the events in Kashmir. (How does one respond? has been a recurring theme in our lives). The Kashmir poems more or less wrote themselves, and this continued with the corona poems and generally all the poems all of which have been written in the last year since August 5th. I (Sunder) write the poems and Sonati edits them to tone down the rants or to suggest a more elegant point of view.

Hope that these poems make you pause, think, enjoy the poetry and get you to write some poems of your own. The world needs more poets.

Photo by Simon Daoudi on Unsplash

With knee on neck

And I can’t brea..

He breathed his last

And he can’t see

What happened next

What happened next

Was that here and there

And everywhere

People realised that

They could not brea..

Until now they

Could not see

That it was because of

Neck and Knee

All over the world

They came in hordes

Black Lives matter

They all roared

Or Brown

Or Pink

Or whatever else

It hardly mattered

What they said

Because the knees were shaking

The shackles were breaking

The necks were straining

The necks were gaining

The knees were deigning

To listen for once

To those whom

They never heard

To those to whom

They had always said

It’s your damn neck

Pressing too hard

Pressing too damn hard on my knee

To those whom they never saw

Even when knee

Was pressed down hard

On neck

I can’t brea..

Was a visceral cry

It let so many others

Breathe at last

And amidst all the

Bangs and clatter

Amidst all the

Twitter chatter

One thing stood out

Each life matters

Each life matters

To he who lives it

Each death matters

To he who dies it

Each life should matter

To you and to me

Each death should matter

To humanity

Photo by Emily Morter on Unsplash

On our first day at

A new school

I met

Berzee, Munaf, Nandan

Venkatesh, Chitcharan, Jude

During recess

After

What’s your name?

We circled warily around

Each other

Finding out

Where someone lived

Did he come by the school bus?

Did he have a car?

Who would take the

BEST bus home with me?

Who had an older brother in school?

Who should I partner with

To play carrom?

What tiffin had they each brought?

Today I look back

And wonder

At those questions

And wonder of wonders

At those innocent times

When after

What’s your name?

There was not

The merest thought of

The menacing follow-up question

There used to be

A newspaper vendor

Sitting on the pavement

On Colaba Causeway

From whom I used to buy

The Evening News of India

For my father

Making sure to finish

Busybee’s Round and About

While walking home

He disappeared for weeks, once

And on his return I quizzed him

Kahaan gaye the aap?

He said, muluk me gaya tha, baba

Where was that?

Uttar Pradesh ki Meerut ke paas

Ek chota sa gaon

Aur gaon ka naam?

Rampur

That was possibly

My first encounter with migrants

But when I started asking

I found that

The Kolhapuri chappal-maker

Near Regal cinema

Was actually from Kolhapur

The shoe-shine boys at Churchgate station

Where Fr Netto used to send us

If our faces weren’t reflected in our shoes

Were from Dhule, Amalner, Erandol. Pachore

The taxi drivers with names like Talwandi and Gill

Were from villages of those names in Punjab

The Irani pao-seller was

Of course from Iran

But more recently

Had come from Valsad

Where was that?

Gujarat ma, dikra

Vegetable and Fruit sellers were from

Unheard-of villages in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh

A veritable geography lesson on the streets

The smuggled TDK and Sony cassette sellers

On the pavements of Flora Fountain

Were all from Kerala

They were the hardest bargainers of them all

But peppering their Tamil-Malayalam with

Mone this and Mone that

Would make me feel

That what I had bought

Was a steal

The Matunga-wala

Who cycled from Matunga

With particularly Tamil goodies

Arisi appalam and kaara boondi

Was of course Tamil

It seemed to me then that

Everyone in Bombay

(With the possible exception

Of Bal Thackeray)

Was a migrant

Including me

Photo by Art Lasovsky on Unsplash

A poet’s vocation

Is dangerous

You stand to lose

Your liberty

Perhaps your life

Worst of all

Your friends

It seems to me that

Nowadays

I just need to

Shake my head

To lose a friend

Should I then

Keep nodding to

Keep them?

We hope you have enjoyed reading Fundamatics, the award-winning ezine published by the IIT Bombay Alumni Association, envisioned as one that is by IIT Bombay (IITB) alumni, faculty and students, and for the same vast community. And, the best part of Fundamatics is that it is completely free and can be accessed by thousands of our alumni who are spread all over the world. But this does not mean that we do not incur any operational costs in bringing the ezine to you. Your financial support can mean that we can continue to remain in circulation and “free” to you, our readers.