There is certain serendipity in writing an editorial on an education themed issue of Fundamatics on the eve of the 70th anniversary of India’s Independence. All the issues that we sought to escape from with the founding of the Indian state in 1947 are, bafflingly enough, still in place. The nationalities problem, as represented most starkly in Kashmir and Manipur; the native Hindu vs.the alien Muslim problem in other parts; the uncertain fate of our underclasses; all of it persists. So one is forced to ask, how fragile – if not failed a state are we?

Let us focus on just the third element, the uncertain fate of India’s teeming poor in the context of education and then ask ourselves the question: have we done enough to realize the promises in the constitution? We have more than 96% enrollment in schools at the primary level and there about 1.86 crore students enrolled in various streams of higher education and yet there has been no major shift in our productivity. There are serious concerns regarding the employability of India’s so called educated millions.

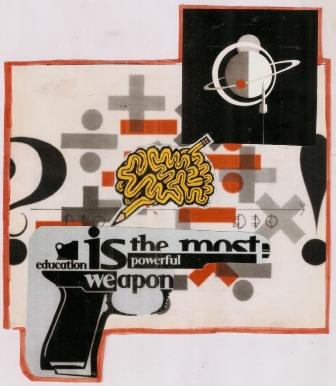

Nothing in India is without the extremes of complexity and education has more of its share than others.

To me the problem seems to be 3 fold – delivery, cost and content. By 2016, approximately 50 per cent of India’s total population will be in the age group of 15–25 years. How do we provide access to quality education at affordable costs to half a billion people so that this demographic dividend, as Parag Saxena points out in his interview, does not become a demographic disaster?

To me the problem seems to be 3 fold – delivery, cost and content. By 2016, approximately 50 per cent of India’s total population will be in the age group of 15–25 years. How do we provide access to quality education at affordable costs to half a billion people so that this demographic dividend, as Parag Saxena points out in his interview, does not become a demographic disaster?

Rote learning still plagues our system, students study to score marks, to crack exams like IIT JEE, AIIMS or CLAT. Our colonial masters introduced education systems in India to create clerks and civil servants, and we have not deviated much from that pattern till today. If once youngsters prepared en masse for civil services and bank officers’ exams, they now prepare to become engineers. As far as content is concerned, year after year our students focus on cramming information without realising that there is a difference between the concept of information and the concept of comprehension and application.

Our system rewards the best crammers. We may have the most number of engineering graduates in the world, but barring the IITs, this has not translated into a resurgence of technological innovation. Memorising is no learning; the biggest flaw in our education system is perhaps that it incentivises memorising above originality.

There are other worrying signs ahead. Our institutions of higher education are also ideological apparatus. The changes at the top of cultural and historical bodies like the Film and Television Institute of India and the Indian Council for Historical Research, unprecedented unrest across universities across India in the past year, the most noted being the unrest in JNU, are all worrying signs towards the state’s efforts at implementing a certain agenda which may exclude rather than include citizens.

For those who doubt this premise, consider this for a moment. In Modi’s India, science grants are being cut and research and development grants are at an all time low, funding of the IITs have also been cut down. So science too is a part of this above mentioned agenda.

The articles across this issue will represent different aspects/viewpoints on all the issues cited above and I am sure it will leave you with food for thought.

But on ending I want to leave you with this thought. It is a fallacy to expect that education has a causal emancipatory and empowering effect. It is what we make with the education that we receive that really makes the difference.

With the rising cost of education (take the 100% fee hike in the IITs), more and more students will now sit across a classroom and look to wring out the maximum value out of their investment. And not just they but their families will connect it to their placements in the job market and the packages that they draw. So far as purpose of education is concerned this is a wholly utilitarian approach and the rebirth Macaulay’s India in a new guise.

The higher purpose of education as pursuit of knowledge, that knowledge itself is and can be a goal in itself, will somehow be lost forever. You may consider me an idealist and a romantic but you will agree that we Indians must do everything that we can so that the next 70 years of India tell a different, better story.