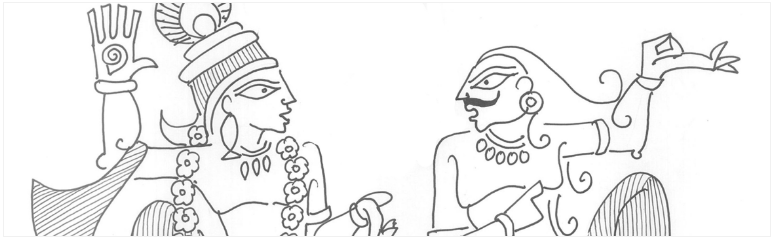

Devdutt Pattanaik writes on relevance of mythology in modern times. Trained in medicine, he worked for 15 years in the healthcare and pharma industries before he plunged full time into his passion. Author of 50 books and 1000 columns, with several bestsellers, he is known for his TED talks, his TV shows especially Devlok, and his innovative views on culture, leadership and Indian approach to management. As any issue on mythology would be incomplete without any input from Devdutt Pattanaik , the Fundamatics editorial team reached out to him with few questions that we thought would be interesting for our readers. We are fortunate that he agreed to respond to queries. Hope that you, our readers, will find his replies and comments illuminating, as we did. The illustrations used in his article are by Devdutt Pattanaik.

1. Typically scientists and engineers distance themselves from mythology. How is it still relevant to them? In other words, what can scientists and engineers learn from Indian mythology and folklore?

Let us define what is mythology. Mythology is a subjective truth, so it comes in the realm of subjectivity. Science and engineering are based on measurable concepts, so they fall in the realm of objectivity. They are just two different words and there is no need to shun either.

To be a scientist, one has to look at the objective reality of the material world. So, when we deal with subjects like physics, chemistry, biology, we work with data collected from the material world. However, the moment we get into the Social Sciences, like Economics, Geography, History, Law, Linguistics, Politics, Psychology and Sociology, certain differences arise. These are called sciences and try to approach problems scientifically, but they also have to constantly deal with human subjectivity. Therefore, the inferences that are drawn in the realm of these sciences can never be considered as fact. The conclusions may be based on facts and data, but they are usually theoretical and hypothetical. Concepts like justice and equality, for example, are not scientific concepts. These are beliefs that one has to work with.

Even in the realm of material sciences, when you start going into the realm of design thinking, (when an engineer has to consider the psychology of the consumer) you again enter a new realm of subjectivity. This is where mythology plays a very important role. Mythology helps you understand cultures: how the Chinese are different from Indians, Indians are different from Americans. So, when you want to understand these cultural differences, you have to enter the realm of mythology.

Mythology helps you understand cultures: how the Chinese are different from Indians, Indians are different from Americans. So, when you want to understand these cultural differences, you have to enter the realm of mythology.

2. In recent years there has been a blurring of boundaries between history, science and mythology and pseudoscience is on the rise so much so that it is creeping into science funding and education. Your thoughts?

This blurring of boundaries is the result of two reasons. One comes from the smug arrogance seen in a lot of academicians who consider themselves as the only source of all truth. The other comes from politicians who state that they understand the needs of the people.

People need to feel good about themselves, people want to feel proud of their past. History, unfortunately, does not do so. History just tells you what happened in the past. Remember, across the world, kings have always had poets by their side to tell of their glory. The artworks that we see on temples and monuments are actually propaganda machines at work. These are then used by historians to understand this recorded past. It is only in the last 50 years that history has reached a refined form where it separates fact from propaganda.

More often than not mischievous academicians, who are interested more in activism than in academia, try to present history in a way that presents one group as villains and the other group as the victims. In fact, the moment you use words like hero, villain, victim, in history, you enter the realm of subjectivity. The moment you call one group the oppressor or the oppressed, you enter the realm of activism and History stops being a science.

When this happens, academia starts being rejected by mainstream society. People then turn towards the hagiographic information provided by politicians. Hagiography refers to biographies that are exaggerated and not realistic.

Medical science cannot answer all questions of health and wellness. There are many vague symptoms that people feel. People feel that a house is negative, they feel gloomy in it. This feeling cannot be explained scientifically, or rather, through a measuring tool. In this case, what we call pseudoscience becomes very important: like faith in crystals, chakras, auras. These make people feel good about themselves and their lives. They play a valuable role in society. Most rituals and festivals are conducted to feel good. This world of feeling cannot be measured and is outside the realm of science.

Life is not just about a mechanistic view of measurable things. As Hindu philosophy says, only the Saguna can be measured, the Nirgun is cannot be measured. The pursuit of spirituality is the understanding of that which is non-measurable.

3. Future Science in Past tales- what are some tales in Indian folklore that would be of interest/relevance to engineers and technologists as tales that were portents of the future?

People need to feel good about themselves, people want to feel proud of their past. History, unfortunately, does not do so. History just tells you what happened in the past.

I find a lot of IIT students obsessed with what is called diluvial geology, the assumption that there existed magical civilizations, with access to magical instruments, before a great, global flood. This is really popular among a lot of IIT folks, about aliens coming on earth and building temples and this is good fun. This is another form of pseudoscience which is popular in the engineering community and has to be seen in the right spirit. It is neither science, it is not fact, nor does it come under the realm of mythology. It is not subjective truth; but fantasies of over-enthusiastic and bored engineers.

4. Mythology often mentions civilizations that were destroyed as retribution by cataclysmic natural events. For example, the biblical floods foretold to Noah or the disappearance of the mythical river Saraswati. How do you view these events in light of the current concern with Climate Change? Do you think these stories may represent civilisational memory of real events in the distant past?

This is related to the previous question.

Imagine you lived in a small village and a flood comes and wipes it out completely. Next year, you build new mud houses and you paint them beautifully and once again a flood comes and destroys them all.

This happened in every river valley civilization. It happened in the Gangetic plains, the Nile Valley and the Yellow River basin. People in Mesopotamia used to build these mud houses which were painted very beautiful, but every year, the river would break its banks and destroy the city. So, the idea of cities being destroyed through a flood is a common phenomenon. The same thing happened to cities that existed at the edge of the sea, tsunamis claimed them. These were not glorious civilizations. Everybody believes that their past civilization was glorious, like Non-Resident Indians having these fantastic images of a glorious India and its villages. When you live far away from a place, geographically or temporally, you start imagining things about it and its death and destruction gets romanticised. The Greeks romanticize Atlantis or the British talk about Camelot, both cities didn’t exist. It is a common psychological phenomenon, where the past looks brighter than it actually was.

5. Is there an ecological angle to the folk stories associated with “minor” gods in the Indian legends and lore? Please do narrate a couple of stories that are less known to the world.

Hindu mythology is generally ecological. Right from Vedic times, there existed a sense of circularity, like water rising from the oceans, taking the form of clouds, the clouds striking mountains, the rains falling and turning into rivers, rivulets, and ponds and ultimately returning to the sea.

The rain which rises above into the sky is associated with Indra, the warrior god, who rides his elephant and strikes thunderbolts to release rain. The mountains are again masculine with the mount, Himalaya, the father-in-law of Shiva. Himalaya is the abode of Shiva. The sea god, Varuna, is the father of the rivers. The generous man who gives us water, who does not swell with pride, even though all the water is returned to him eventually. Varuna’s seven daughters are the Sapta Sindhu: Ganga, Yamuna, Krishna, Kaveri, Narmada, Tapti. They eventually join their father Varuna and an ecological angle is seen.

Ecology is also seen in the Sam Veda. All the hymns of the Vedas are classified into forest hymns or Aranyagan, or settlement hymns or Gramgyan. We see a sense of awareness of the domestication of nature, which takes away its wildness, as well as diversity.

Across India, in small villages, there have been places where is Devarayi, or sacred groves of the goddess, which no one could use as pastures or for cultivation. These groves were allowed to grow naturally. People visited these places only once a year, during the goddess celebrations, to offer the goddess the harvest and her sacrifice. This is the way of managing biodiversity. It is a simple technique that can be revived even today, where every farm and every village can give away a few acres of its land and let it grow wild, to allow biodiversity to thrive.