Mythology in the Modern Age

Guided by the hands of Reason and Science, one would imagine the modern age has little place for endless epics, speculative reflections and metaphysical meanderings. While Mythology may have occupied centre stage in times of yore, one may well ask what place it has in today’s world. The answer is more complex than it appears.

One area where Mythology has wielded a heavy hand is during the Indian Freedom Movement. From influencing the methods and philosophy of leaders like Gandhi and Tilak, to providing a subject upon which artists built nationalist visions, Mythology became the guiding force of History.

Theatre: A Spring Board for Change

Theatre was by no means a new phenomenon in India. Nor the use of mythological themes, which had been popular since the times of Bhāsa and Kālidāsa. But during the British period, these themes were recast in imaginative ways to communicate a nationalist message and get around British laws of censorship.

In 1872, a play called Nil Darpan was staged in Calcutta by the Calcutta National Theatrical Society. It was a scathing exposure of the oppression by British indigo planters of the impoverished Bengali ryots. The English were not impressed.

The play was ordered to be stopped forthwith. Soon thereafter, the Dramatic Performances Act, 1876 was enacted to check the revolutionary impulses of Indian theatre by empowering the Government to prohibit dramatic performances found to be scandalous, defamatory, seditious, obscene, or otherwise prejudicial to the public interest.

The menace had been nipped in the bud. Or so the British imagined.

Dressing Nationalism with Mythological Hues

While the British clamped down on nationalist theatre, they did not interfere in religious plays. They did not listen carefully to religious/mythological dramas and carelessly stamped them for approval.

This gap, was all innovative playwrights with nationalist fervour needed, to slip through the door.

Radheyshyam Kathavachak

Kathavachak was one of those brilliant prolific writers who penned several plays in this unique genre.

One of his most famous plays was Bhakta Prahlad, outwardly the story of Prahlad, son of King Hiranyakashapu who stood up against the tyranny of his father. At a deeper level, it urged Indians to stand up against the British. Just as Vishnu supported Prahlad although he was weaker than his father, Indians too could expect divine assistance in their fight against the British, was the underlying message of the play. The play acquired national fame and ran to packed audiences.

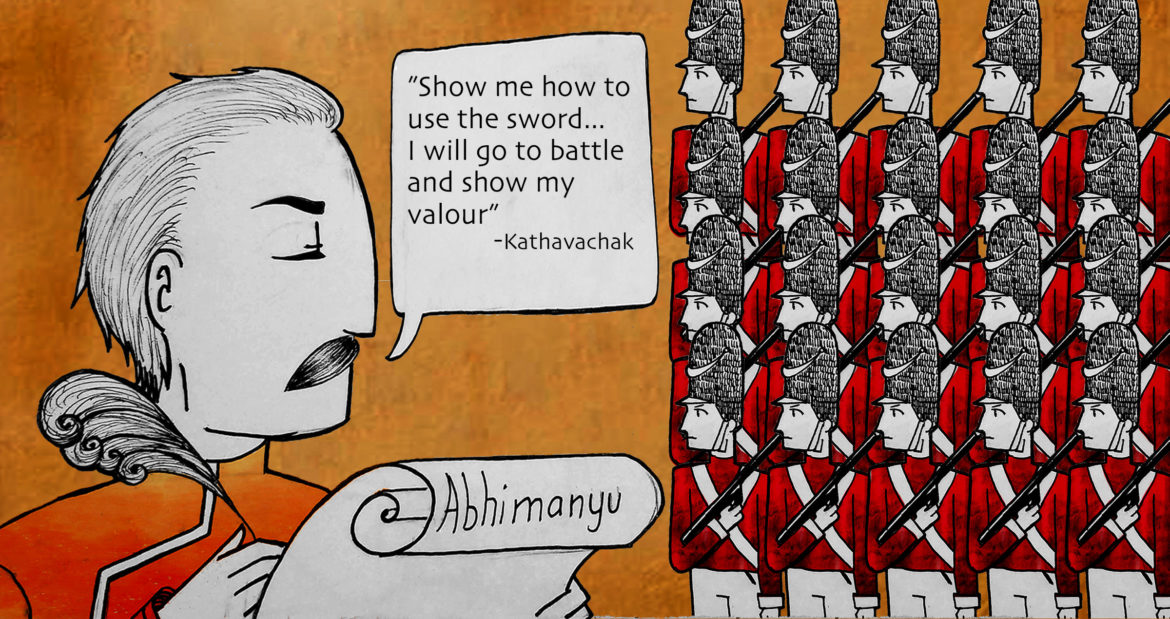

Another of Kathavachak’s plays that created a stir was Vir Abhimanyu. It urged viewers to take up the challenge just as Abhimanyu, son of Arjuna, had done bravely by entering the chakravyuha at Kurukshetra. Although the enemy was stronger than him, Abhimanyu fought on, sacrificing his own life for the sake of the cause. In the play, Shubhadra urges her son to fight and Uttara, Abhimanyu’s young wife, sends her husband proudly into the battlefield. ‘Show me how to use the sword…I will go to battle and show my valour’ says Uttara to Abhimanyu, prompting women to join the fight for freedom.

Subramanya Bhāratiyār

While Kathavachak created a tumult in the north, Subramanya Bhāratiyār, one of the greatest Tamil poets, did the same in the south. Seeking inspiration from the Mahābhārata and the local terukuttu tradition of Tamil Nadu, he penned a poetic dance-drama that became a lyrical vehicle embodying the message of freedom. His Pāñcāli Capatam (The Vow of Draupadi), is a popular piece in dance performances to this day.

The scene it draws on is familiar to most of us. Draupadi has been lost in a game of dice to the Kauravas and is thereafter disgraced before the assembly of nobles. This is the scene Bhāratiyār picks to transform into a political metaphor.

Through selective phrases, he compares the humiliation of Draupadi to the colonial oppression of India. The victimized Draupadi becomes Bhārat Mātā and the Kauravas symbolize India’s colonial oppressors. Draupadi is referred to as Amman or Goddess in certain parts of Tamil Nadu, where she is revered as a village goddess. Bhāratiyār draws inspiration from this background and turns her into Mother India.

This play had such a political impact that it was outlawed by the British.

Krishnaji Khadilkar

One of the most dramatic and impactful mythological plays of all during this period (and my personal favourite) is Kichak- Vadha (Slaying of Kichaka), written in 1907 by Krishnaji Khadilkar, the right-hand man of Tilak, editor of the Marathi newspaper Kesari.

The story is set during the last year of the exile of the Pāndavas, which they spend in disguise in the court of King Virāta. Kichaka, a minister in the king’s court, attempts to molest Draupadi during this time. While pacifist Yuddhishira does not intervene, radical Bhima is infuriated and kills Kichaka.

While at the literal level, the play portrayed the last year of the exile of the Pandavas, at a deeper level, it sent out a strong allegorical message. It encouraged the radical approach of the Extremists and mocked the pacifist approach of the Moderates.

Several clues pointed to contemporary political parallels:

- Kichaka represented Viceroy Curzon;

- Draupadi represented India /Bhārat Mātā and her dishonour represented India’s shame under foreign oppressors;

- Yudhisthira represented moderate nationalists like Gandhi who were not willing to take extreme steps for winning freedom;

- Bhima represented the extremists who were willing to take extreme measures to win freedom;

- Bhima’s violence implied the ultimate triumph of revolutionary means.

The play even gave Kichaka lines like ‘rulers are rulers and slaves are slaves’ – words of Lord Curzon – leaving no room for doubt about contemporary parallels. So explosive was this play that it prompted the murder of a British official named Jackson inside a theatre in Nagpur.

On 27th January, 1910, the British banned the play.

This was the period in History when theatre centred around mythological themes, became a tool to forge a new national identity, which in-turn became a spring board for social change. Mythology – repackaged and re-imagined, packed a powerful punch in line with the needs of the age.

And in case you’re wondering – Yes, the Dramatic Performances Act, 1876 still exists in our statue books!