Illustrations by Frits Ahlefeldt

The Reality on Ground

A road trip to Vrindavan is a reality check on water. An Ashram – a social network for the elderly is in need of an economical water solution. We stop at a prosperous-looking farm on the banks of the river Yamuna. A crop of mustard is being sowed. The owner comes with an earthy grin and offers us hot tea. We chat and learn that the electricity is erratic, so he leaves his pumps on for irrigation and floods the farm. We talk about productivity, water, irrigation, and fertilizer. He is oblivious to most of it, including drip irrigation. After all, water is ample and electricity-free so why bother about such things? We have practiced this for generations. Is the government paying to use it? A further small talk over a hot kachori reveals that the water table has been falling, pump failures are frequent, the water smells bad but seems to be working well for the crop. What the farmer is pumping is the discharged sewage water from upstream which has contaminated the groundwater. It reminds me of a cousin saying, “The rivers of India are at direct communication with the lower end of the gastrointestinal tract of those who live upstream and with the upper end of those who live downstream.” For me, the trip yields no business. I am ridiculed by the water budget and treatment scheme. The learned managing committee of retired professionals resonates, if the water is free the treatment scheme should be free too! The tell-tale signs of climate change and resource exploitation are evident at Vrindavan. The water table is falling, the farm does not yield as much as it used to, the summers are hotter as evident from a few wilting trees and Yamuna has lost its vigour throughout the year.

We drive through the winding roads of Pauri, Uttarakhand on behest of a concerned minister. We stop at a dozen water treatment plants on banks of rivers. Sample water, and test it. The results are the same – excellent physical and chemical properties but all test positive for E.coli – an indicative bacterium for fecal contamination. The villages we traverse have open gutters filled with plastic or none at all. The sewage finds its way into clean water. The ray of hope is the pine trees being replaced by the local bhaanj which retains water in its deep taproots and provides potable water round the year. A lesson in sustainability. Humans have gone back to their routes, rejecting the ‘modern’ ways of managing forests and water.

Families in the villages have to walk fifty to a hundred meters to fetch water for daily use. The sanitation facilities are common and kept clean. The water from the common toilets is let out without treatment. The thriving shrubs downstream of the discharge are a testament to the presence of nutrient-rich untreated sewage.

Towards the end of the journey, we stop at the local kirana store to buy a bottle of water. It is closed. A neighbor proudly offers us ‘pure’ water from his proud new possession, a RO water purifier, a sign of new-found prosperity from selling land. We drink, almost distilled water without bacteria, and head towards Rishikesh.

Again, the telltale signs of climate change are evident. Reducing tree cover, heavy erosion due to bursts and floods. The aging treatment plants run with inefficient motors installed through an L1 capital cost proposal, consuming far more power and thus contributing to carbon emissions.

We shift gears to the affluence of Mumbai. Alibaug – the Hamptons of Bombay, is a quiet hamlet 14 km south of Mumbai as the crow flies. The million-plus dollar weekend homes have a perennial problem of seeking the elixir of life, either from the wells on their property or from tankers which roam the pot-holed roads as the messiahs for the lush green lawns and swimming pools. There is no piped water in Alibaug! Sewage and waste management do not even get an honorable mention and rainwater harvesting is a great topic for WhatsApp University! After all, there is no payback for rainwater harvesting and storage compared to the cost of a tanker! The locals have their hand pumps and the gram panchayats provide a ¾” line for 1 hour of water. The irony is that the area receives one of the highest rainfalls, almost 2400 mm per year. I visit a friend’s house for a pro bono consultation about his water woes. The three borewells he has, play musical chair every monsoon – who will be the saline one that season? The salinity level changes every year thanks to the intruding seawater. Again, a telltale sign of impounding effects of rising sea levels due to climate change rushing into the voids created by over-extraction of groundwater.

Water in India

India receives 4000 km3 of precipitation every year through a fairly predictable monsoon. The majority of it occurs in four months from June through September. The intensity and the patterns vary because of the geography and regional climates. Half of the precipitation runs off to the sea, balance is used to charge the surface and groundwater. The agriculture sector is the largest consumer of water at 83%, followed by the power and industrial sector at 6% each and potable use at about 5%. The quantum of water we receive will remain more or less persistent but the demand will grow on all fronts.

Access to water is a quagmire. The agriculture water is virtually free, potable water is charged but does not cover the cost of operations. The industries are charged for water. It partially subsidies other uses. As a consequence, the crop patterns are skewed, productivity with respect to water is dismal, and depletion of groundwater is alarming.

Access to potable water is even more disturbing. In rural areas, 12% of households have access to piped water. In urban areas, this number is 40%.

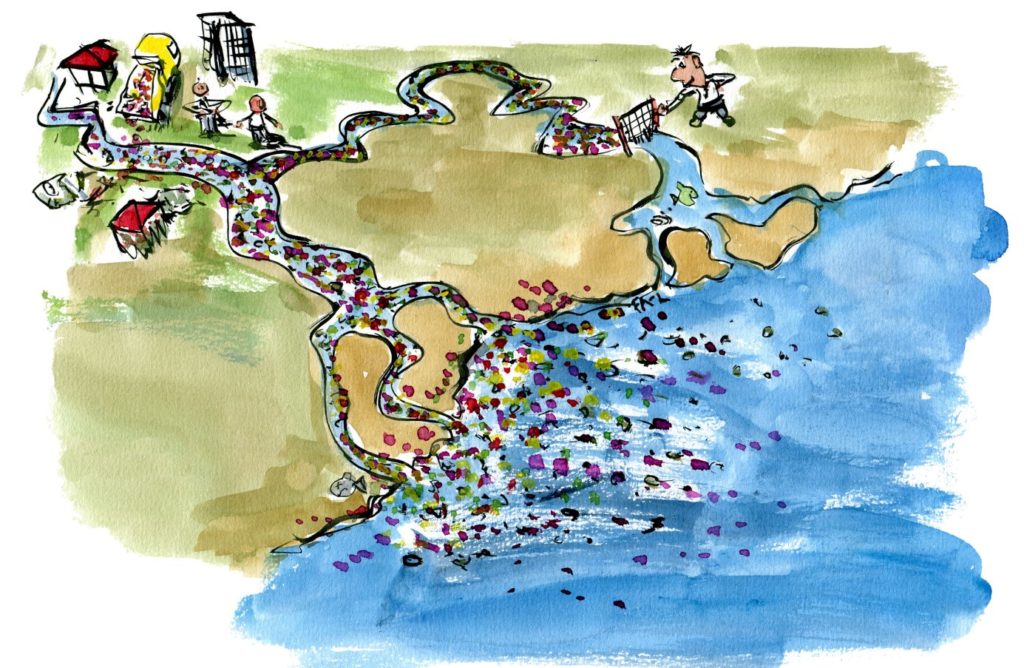

The sewage situation in India is dismal. We generate 78 billion liters of sewage a day out of which 23 billion liters are treated. The balance goes to our water bodies with partial or no treatment.

Storylines of water running across India are similar only the plots twist and turn: Water is available, access is not. Sources are drying up. Floods are galore. Droughts are rampant. Quality is dubious. Salinity is increasing. Water treatment does not work. Water is not priced but de facto privatized through tanker lobbies. Agriculture receives virtually free water. We buy some of the most expensive water in bottles. The majority of the polity is oblivious to the nuances and complexity of water.

The heavy burden of the past water woes, tattered and inadequate water infrastructure, the present reality of climate change and global warming have accentuated the water situation. It needs to be tended now with a heightened urgency to prevent an apocalypse. We have very little room to maneuver the situation in time before we are squeezed against a rock and a hard place.

Climate Change and Water

Climate change is a reality, not a point of debate. In a short span of the last 300 years, the earth has seen a million new chemical entities, greenhouse gas emissions, more fossil fuel burnt than any time in its life, concrete jungles, and forest land cleared for agriculture and urbanization. It is an equivalent of a Dirac Delta function of the earth’s environment. The decay of this function over time has manifested as global warming as the major outcome. The implications are dire: Increased transpiration and water needs for vegetation and humans, expansion of sea levels leading to salinity intrusion, dwindling freshwater resources, local hot spots, extinction of habitats and biodiversity, and increased freshwater demand. Extreme weather events leading to storms, floods, droughts, erosion, seawater ingress, and destruction of property and life are a daily affair. All these affect the availability of fresh water for human use. Economically, more than 39% of Indian Banks’ portfolio is exposed to sectors that face high levels of operational risk related to water and climate change. Worldwide, flood risk due to rising sea levels and cloud bursts are the major risk factors for real estate.

A Relook at Water

A nation of 1.3 billion people has to be fed and its thirst quenched. Economic growth which improves health and the standard of living needs to be addressed urgently. The water resources, some of which are shared with other countries have to be addressed for long-term water security.

Ownership and Governance

A 100-year water vision is a necessity, not an also-ran agenda. Civilizations have died and thrived because of water. The vision needs to recognize that water is a basic necessity, not a political tool to manipulate the republic for winning elections.

Whom does the water belong to? This debate is indispensable for water sustainability. A clear answer is a must for governance. A central regulatory agency with geographical sub-divisions may be a good idea with appropriate structures and human resources. Lucid and executable policy and laws are a necessity for sustainable water. Data, water mapping, and on-line water analytics should be used to govern water resources and usage. Water needs to be regulated not politicized. How we bring about these changes is a Herculean task.

Investing in Sustainable Infrastructure

The current realization of using natural systems for the storage of water and mitigating effects of climate change are well recognized. Investments should be made in natural systems for water sustainability and mitigating the effects of climate change. A number of cases are quite promising. An oak forest over 10 km2 serves as a nice example of a watershed to provide potable water to the town Shimla. Rather than damning the rivers through dams, an ecological flow should be ensured in the river systems of India for groundwater recharge, development of wetlands to mitigate floods and provide habitats for biodiversity. Rivers are like a rubber band. They flex themselves to find their way when fertile silt is deposited. Constricting them is a definite way to increase floods and destroy biodiversity. Could we have reimagined Narmada and Tehri projects to be far more sustainable? Can’t the immense solar potential of Kutch be unleashed to develop revolutionary solar desalination technology and create a pioneering industry? It could have alleviated the need to submerge vast forest cover and displace more than a million people from their lands.

Groundwater should be considered as a water bank rather than a water source. The extremities of climate change will then allow us to draw the water reserves in drought and replenish it in good years. For a successful ground resource strategy, mapping of aquifers and development of recharge methods and structures are essential along with withdrawing and groundwater management strategies. It has to be a key part of the 100-year vision and a major element for sustainable water.

Human Behavior and Resources

Besides economics, education is the second lever for behavior change. Sustainability as a part of the high school curriculum will bring this change and create young minds who would be interested in working with water. They can be the change agents. This approach can lay a strong foundation for developing the water champions who address all aspects of water.

Behavior change has to go through a continuous path for it to be imbibed. Making small but continuous changes that do not drastically disrupt the lives of people is essential for a successful behavior change.

Pricing Water

Today, water is virtually free. It discourages any discretion in use. It needs to be priced for behavior change and economic growth. A number of issues need to be addressed before a well thought out pricing strategy can be introduced. An equitable and affordable basic need has to be met. Water needs to be metered. An infrastructure to deliver has to be created. A block tariff model may be used to address equitable distribution as it has been done successfully in Durban. Priced water assures a number of advantages: The consumer can demand quality, quantity and uninterrupted supply, it allows for upkeep and modernization of water supply and importantly forces a behavior to use it responsibly. It allows for improved public health. The reliable and confirmed water supply reduces a large risk factor for farmers. It will help them earn a better living through multiple and high margin crops. Water pricing can make agricultural produce more market-driven.

Pricing of water allows for revenue generation and thus a market to raise funds for water infrastructure projects.

Sewage a Priced Resource

Sewage treatment warrants an incredibly urgent attention because a dismal 30% of it is treated across the country. The two major implications of untreated sewage entering the environment are contamination of clean water sources and public health hazard. Sewage is rich in nutrients for agriculture. It can be treated well with Phytoremediation Technologies for agriculture use or with hybrid technology for non-potable reuse such as cooling tower make up. Enablers for realizing value out of sewage are metering, robust and well managed infrastructure and compliance with the standards. These will allow for multiple use of water before discharge, protection of clean water sources and improved public health.

Role of Technology

Technology will play an increasing role in water sustainability. Agriculture consumes the largest quantum of water today. Today, the penetration of micro-irrigation techniques is less than 3% for all irrigatable land. A yearly target of bringing 2-3 % of land under micro-irrigation will preserve water resources and improve agricultural productivity on all counts. The key to adaptation is creating conducive market conditions through metering, pricing and enabling free markets for agricultural free produce.

The price of decentralized solutions for water treatment is reducing. A cost-benefit analysis of large pipe networks versus decentralized water solutions needs to be addressed. The decentralized solutions reduce large capital outlays, allow for technology customization for water quality and upgradation.

India requires special technologies to address natural contaminants like arsenic, fluoride and iron. We have to deal with them as they are a part of our geology. The increasing affluence will lead to the ingress of pesticides, drugs and excessive fertilizer in water sources. Advanced techniques for water treatment like ozonation will be needed in the future. We need to develop multiple approaches to address contaminant issues.

Reverse Osmosis (RO) is an enigma for India. RO is an expensive technology. To successfully run it, trained manpower, energy, and significant maintenance are required. The environmental footprint of RO is poor. It is power-hungry, generates substantial saline waste and the de-scalants are discharged into the environment as waste.

Using reverse osmosis (RO) or desalination for salinity control, especially for industrial wastewater is necessary. Re-engineering waste-water generation is the need of the hour. As far as possible RO is to be avoided for potable water treatment. Can’t we think of rainwater recharge to reduce salinity for land locked regions? Or use solar energy for desalination using electrodialysis? Adaption of RO needs critical, integrated and holistic thinking before investment. It is an easy way out but a steep price to pay in the long run.

The paradox of sustainable water is a colossal epic. Securing water today will reflect the empathy, courage, imagination and innovations which have gone in providing a sustainable future for the coming generations. It is towards the future of sustainable and abundant water that we should endeavor.

1 comment

Around Madras definitely; (and probably around other cities,) owners of farmland do not grow stuff to eat: they just farm the water.

The demand from the tankers is always there; Madras always needs water; electricity is free for farmers; so…

This perverse scenario needs changing, but the change will not happen by itself.

Equally perverse to me is the carbon offset idea: You pay someone to “use their pollution”. This idea has been instituionalised and has therefore come to be culturally accepted.

But is there any real difference in the two scenarios?