(This article was written in October, 2017.)

Writing about women in IIT, starting off with my memory of being there almost four decades ago, is a difficult task. And it is not because memories fade and things change, but because some memories refuse to fade and some things refuse to change. This is of import today because as I write this there has been an attack in a University on women students who were protesting against sexual harassment and the discrimination that they face on campus. They were fighting for more proactive measures by the University to address the harassment they faced from the men on campus, the fact that the streets were not adequately lit, and also that they were being locked into the hostel earlier than the boys and not being given similar food [1].

Over the last couple of years, as these voices of rebellion of women students have risen from across the country – DU, JNU, AMU, Mumbai University, Allahabad University, SRFTI, BHU … (and I am sure many others that did not make national news) – I am reminded of the year 1978-79 when a small bunch of us were protesting similar discrimination on the IIT Powai campus. We were students of IIT who resided in a students’ hostel like the others, but who did not experience the campus like the others. We were barely 75 women in the “Ladies Hostel” (or LH as it was then known). There were almost 3000 other students in nine other hostels, named Students Hostel 1 to 9 (H1 to H9) on campus.

Not only was the name assigned by the authorities a marker of our difference, we were located far away from the others, away from the hub of student activity, apparently safely ensconced on the fringe of faculty housing under the watchful eye of the Director from his bungalow. It is another matter that this proximity to the Director made it easier for us to go petition him from time to time for the room shortage that we faced every year from 1977 onwards (till very recently I hear). Or to protest against the ridiculous seven-foot boundary wall that was once proposed because an intruder had entered our hostel one summer night bringing much excitement in our dreary summers.

Not only was the name assigned by the authorities a marker of our difference, we were located far away from the others, away from the hub of student activity, apparently safely ensconced on the fringe of faculty housing under the watchful eye of the Director from his bungalow.

The rules on paper for all the hostels may have been the same, but the way in which they were imposed on the students of our hostel was very different. There was no curfew for the other hostels and in reality anyone could enter and exit these hostels. It is another matter that we were wary of going on that side of the campus. The true character of the cream of the nation, the so-called “above average IQ” person who resided in the students’ area, is best left undescribed because it is a known secret to all alumni of IIT.

In this situation, as students of the campus we raised the issue of changing the name of the hostel from Ladies Hostel to a respectable Students Hostel 10 (just like all the other student hostels); we demanded that the curfew on us be lifted; and we wanted to formulate our own rules so that all guests (irrespective of gender [we only thought in the binary then]) be allowed conditional entry into the hostel with the conditions being those that we collectively arrived at as residents of the hostel. We all came from different backgrounds and so arriving at agreements on rules was not easy, but we managed to arrive at workable solutions that were agreeable to all the residents of the hostel. It meant long discussions amongst us about issues of privacy and safety. Those lessons about living together with different points of view and of consensus building and dialogue as methods of democracy refuse to fade.

We dreamt big. And we managed to get all that we wanted, implemented.

How we achieved the change was just that – we did it. It was our hostel. We decided how we wanted to live in that space, what we wanted to call it and we just started doing exactly that. We did not have other examples before us. We just did not accept the fact that we were being treated differently. We saw ourselves as students of the campus. This particularity of being treated different just did not seem right to us and we were using the logical training that we were getting to address it.

The interesting thing is that we managed to do all of it without active intervention from our teachers or the institute. We were happy to have a non-interfering warden, someone who was an independent woman and treated us as autonomous young women. And much to the credit of IIT authorities then, we did not face any backlash for deciding our own rules and nor did we have to agitate a lot. One needs to say this because in the present moment there are many universities where the authorities have been ruthless in the ways in which they deal with such actions.

Obviously it was a different time. It was post Emergency when it looked like anything could happen. It was the beginning of this new articulation of feminism, unlike the present when there is a steady backlash against feminist articulations, as the world realises the full potential of what real equality means to the existing social order. So while gender equality is a catchword, the meaning of equality is different especially for those in authority. The confusion around the meaning of equal access, leads to inclusion that is half hearted. In this context I wish to initiate a discussion on the issue of number of women students in IIT.

The government is worried that in spite of it being more than six decades since the first IIT was set up, the percentage of women in IIT, especially in the flagship B Tech courses, is not rising much above 8%.

The government is worried that in spite of it being more than six decades since the first IIT was set up, the percentage of women in IIT, especially in the flagship B Tech courses, is not rising much above 8%. Worse still, even though around 12% women qualify, only 8 to 9 % actually join an IIT. The reasons have been identified as largely related to the situation of women’s education in the existing patriarchal society. And so one of the suggestions for achieving a larger percentage is of increasing the number of seats for women who qualify the JEE Advanced by addition of supernumerary seats (in addition to the existing seats). This is a scheme that shall be implemented by 2018.

While I do agree that part of the problem is the steadily increasing cost of preparing for the JEE to get into IITs, and the reluctance of parents to send women to the coaching classes to bring them on par with the men students who they compete with for admission, there are many other issues as well. We need more data and analysis. We need to compare data of all the IITs to see if the trends are similar. We need to compare programmes and disciplines with other enrolments in public institutions of repute across the country. IIT has more students coming in for postgraduate programmes and hence not through JEE. The total number of women in IIT also is lower than the national numbers for science and engineering. Fundamentally, since this is about the number of women coming in, the question is as much about society’s perception of IIT and IIT’s projection of itself, as it is about society’s patriarchal notions about what women can and cannot do.

It looks like those who succeed in IIT are usually men. Look at the number of women awarded distinguished alumni awards till date – five out of the total of 182 (merely 2.7%).

Prajval Shastri in her article in the Scroll highlights some of these issues when she asks the question of what have the IITs done within their own systems to show that they are spaces where there is gender equity [2]. She rightly asks what is it that the IITs are doing to show that these institutions are safe and welcoming of all genders. In 2005, Prof Sukhatme and Prof Parikh writing on the issue “Why fewer women in IIT” raised similar questions [3]. They suggested a more “proactive stance on the part of the Institute”. This included but was not limited to showing to the world the kind of facilities that exist for women students, featuring women alumni in material about the Institute, getting alumni to persuade women students to join IIT, and also exempting women students from fees as well as providing scholarships to them. Essentially what both these analysis ask for, is more reflexivity within the Institute about its own practices and policies towards women students.

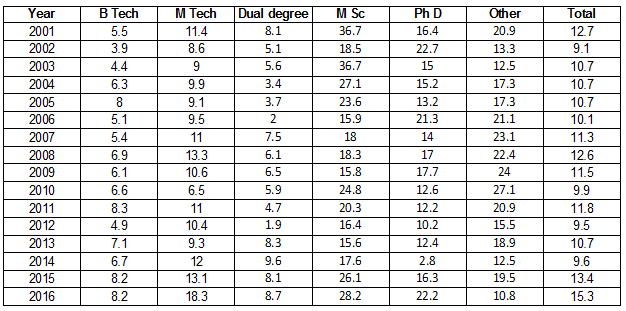

And for this it is not enough to just look at the number of women students coming in through the JEE. A more detailed analysis of all courses and number of women within these is important also. I looked at the data of all students that passed out of IIT disaggregated by degree conferred for the last sixteen years [4]. It is obvious that the numbers in the B Tech and the dual degree programmes fluctuate between 5 and 9%. The magic figure of 9% is crossed once in the dual degree programme. It is these low figures for women students coming in through the JEE, that prompt measures like extra seats to address the disparity in the intake for the B Tech programmes.

A closer look at the other figures, however, shows that the situation is not much better for those that do not come in through the JEE. The number of women students at the M Tech level or in the MSc programmes and even the PhD programme which includes the HSS does not show any marked improvement over this same time period. In fact the MSc actually shows a dip from the earlier percentage which was at around 35% and above. The total number of women in IIT also do not manage to go much above the 10% mark in the whole time period. In fact it hovers between 9 and 12% with the last two years (2015 and 2016)showing an increase accounted for mainly by a sudden increase in the total strength of MTech students. There are some unusual dips in the numbers around 2006 and 2012. These need to be explored further to know if there were any reasons why these sudden plunges happened.

This data is from this millennium, a time period in which IITs have been in the news thanks to the active alumni network that has been activated consciously for fund generation. Could this be a possible deterrent to young women aspirants? I decided to check this further as I was writing for the alumni newsletter.

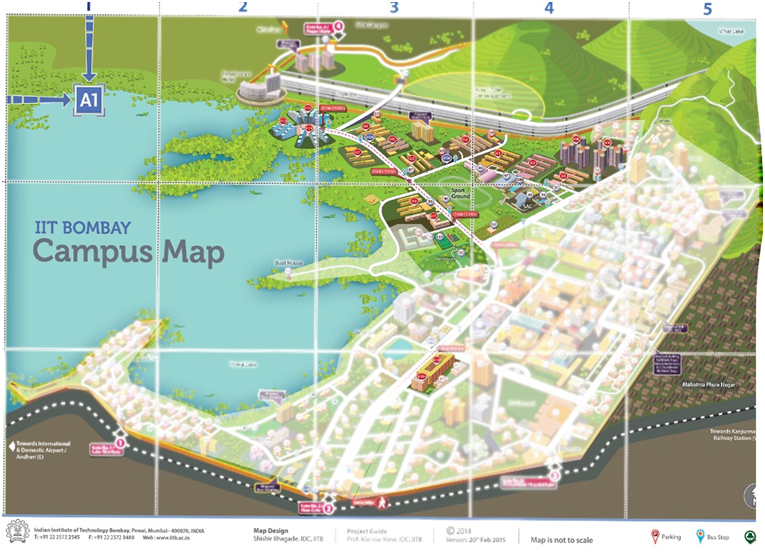

The isolation of Hostel 10 from all other student activity stands out and this is the present hostel which is a much larger version of what existed in 1977 and even till the early 2000s.

It looks like those who succeed in IIT are usually men. Look at the number of women awarded distinguished alumni awards till date – five out of the total of 182 (merely 2.7%). The distinguished alumni awards were started in 1983 and have been regularly given as an annual feature since 1996. The first woman gets it in 2004 and she is a Physicist. The next woman was awarded in 2012 and since then there have been three more, so some efforts are definitely being made, but there need to be much more. Maybe we need a real analysis of number of students and their proportionate representation in the success stories. Either the women really do not succeed or they are not being counted and remembered. Maybe success means different things to different people. If women alumni are not active in the work of alumni association, there is need to ask them why.

In “Monastery, Sanctuary, Laboratory”, Rohit Manchanda has taken special efforts to get women in IIT into the story [5]. The book even has a small section on the experience of women in IIT. So it is not lack on his part, but what gets recorded there is not encouraging for aspiring women students. It is indicative of the way in which women get mentioned in IIT lore itself that keeps reinforcing the feeling that women are separate from the story of the IIT student.

As a woman student said in InsighT in 2001, “Believe us, being a minority community is no picnic…having a classful of guys when you are the lone girl is no girl’s dream come true.” But in the general narration, the absence of women in the story is to highlight the suffering of the IITian who has to make do with no women around him. (All use of pronoun here is specific.) Be it advice to a topper to go slow and get some pastime like holding hands with some fair damsel from LH (pg 303) or the mention of the first increase of women from 1 to 6 in 1962-63 getting a comment like, “The ratio of girls to boys had pole vaulted from the somewhat unnerving 1:875 to the far more bearable 1:190”. One wonders what the women in LH thought of the former instance which is a suggestion by a faculty to another fellow student and whether becoming 1 to 6 really made anything bearable to the women or the men.

Or take for example the way in which Vijaya Korwar is spoken of by faculty as “incomparably the best girl student we have has at IIT Bombay.” (pg 305) For someone with the highest CPI from 1974 (when the system was introduced) until 1979 and must still be among the highest few at 9.95, should she not be remembered as one of “our finest students”? I definitely wish she were.

It is this othering and the way in which they/we do not “naturally” become part of the story that irks and discomforts. The point of these examples is to urge a serious evaluation of the ways in which we speak and think of women in IIT both as teachers and alumni. Women are there after having struggled as much as the men to get in and succeed in the gruelling academic schedule. Treating them as the other, filters through in more ways than we imagine and maybe a good gender audit is essential if we really want women to be part of the IIT story.

And that brings me back to where I began. Way back in the late 70s we fought to be recognised as equal students on campus. We challenged some of the obvious differences in the way that we were being treated. A lot of what we went through on campus we did not talk about. The harassment that we faced as women students from our peers and our teachers, the snide remarks from our own classmates about “how our lives were easier since the predominantly male faculty obviously favoured the women” (statements reeking with the assumption of heteronormative desire and power), the ways in which we worked harder to get recognised for ourselves – we have not spoken of it enough like women from anywhere else.

The meritocracy, the genius of the IIT students, the brilliance and the nerdiness, all hid the underlying mistrust if not misogyny in all the interactions. All I can say is that making the campus more physically accessible to us through opening out of the hostel and the hostelites, helped bridge some of these gaps marginally. I shudder to think of the cat calls that would have continued to be a part of our life every time we dared to walk past the boys’ hostels had we not been bold enough to lay claim to the campus as students. Opening up helped us bridge the distance that the planned campus has imposed.

In recent times, while we are studying discrimination in higher education institutions, we have looked at the architecture and planning of campuses [6]. IIT campus and location of H 10 on it has been like a beacon which led me to look at other campuses to unravel the stories that this tells of inclusion and exclusion. Hope to share that information in the public domain soon but this picture from a schematic map of IIT Bombay campus speaks for itself as far as inclusion of women students in IITB campus goes. The isolation of Hostel 10 from all other student activity stands out and this is the present hostel which is a much larger version of what existed in 1977 and even till the early 2000s.

These metaphorical and physical distances have to be bridged to make IIT accessible to women, else a mere increase in access to seats will not lead to any major change that we seriously want. In fact considering the emphasis on merit that this campus and its inhabitants have and as we have seen through testimonies of students from other margins like those of caste, class, language, region, and ability, any attempt at getting women through reservations will boomerang in making them seem more undeserving. All those marginalised by society deserve affirmative actions, but it has to be done as a matter of right and due procedure, and not be seen as mere lip service or ticking of the right boxes. Access alone is not enough.

These metaphorical and physical distances have to be bridged to make IIT accessible to women, else a mere increase in access to seats will not lead to any major change that we seriously want. In fact considering the emphasis on merit that this campus and its inhabitants have and as we have seen through testimonies of students from other margins like those of caste, class, language, region, and ability, any attempt at getting women through reservations will boomerang in making them seem more undeserving. All those marginalised by society deserve affirmative actions, but it has to be done as a matter of right and due procedure, and not be seen as mere lip service or ticking of the right boxes. Access alone is not enough.

[1] http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/banaras-hindu-university-on-the-boil/article19746481.ece

[2] PrajvalShastri. “The IITs want more women students but can extra seats be the answer?” Scroll , April 29, 2017. Accessed on 15 Sep 2017.

[3] S P Sukhatme and P P Parikh “A Silent Revolution: Assessing Output of Women Graduates & Post-graduates from IIT Bombay”.

[4] This data is collected thanks to the efforts of Damayanti Bhattacharya, Sharba Sen, and Vandana Shirsat at the IITBAA office. They had to cull this data out of convocation records as no other gender disaggregated database is available as of now. Making one could also be one of the priorities of the Institute.

[5] “Monastery, Sanctuary, Laboratory”, Rohit Manchanda

[6] This is part of An exploratory study of discriminations based on non-normative genders and sexualities, a project located at The Advanced Centre for Women’s Studies, TISS, Mumbai.

4 comments

Wonderful article. As a matter of trivia who were the first UG to graduate from IITB? If my memory does not fail me :

Tejaswini Saraf and Rekha Rege circa class of 1966.

Hello Everyone : Correction Tejaswini Saraf is my second cousin and did graduate in 1966 EE However Rekha Rege was class of 1968 CHEM ( How do I know : My brother and Taejaswini studied together and my brother Jayavant Parulekar was 1966 Civil Hostel 4 ( I am 1969 ME Hostel 6)

Shashi Parulekar Troy MI USA Ph 248 225 7611

Hi, For those interested in knowing more about the first few ladies to graduate from IITB, this gem of an article from the recent Fundamatics issue has some information about them, as well as the story of how LH / H-10 began.

https://fundamatics.net/origin-of-the-ladies-hostel-on-the-iitb-campus/

Out of genuine interest: where would these two technical minded brilliant young ladies of the 1960s be at now?

What career did they pursue? Being an old Mumbaikaar, I look back at those halcyon days with great fondness and remember the wonderful young people of a bygone time. Mumbai breathes differently now