Artwork by Prof. Arun Inamdar

IITB was a very special place. H10 at IITB was an even more special place.

In my first semester, my brother was in town on a visit. We went out to dinner with a friend. It got pretty late by the time we finished. Must have been close to midnight. By then worries had been expressed numerous times: What is the closing time in your hostel? They were far more anxious than I was (which was precisely 0 on a scale of 0 to 10, or 0 to any number, for that matter!) and that amazed them.

When I said ‘there’s no such thing’, they were incredulous. How come a girl’s hostel doesn’t have restrictions? They were mightily impressed. All the way from Bandra to Powai to drop me back, they kept asking the same question. This was 1980, and the notion that hostels for girls can exist without these ridiculous rules was simply not easy to believe. Even now ‘working women’s hostels’ have curfew times!

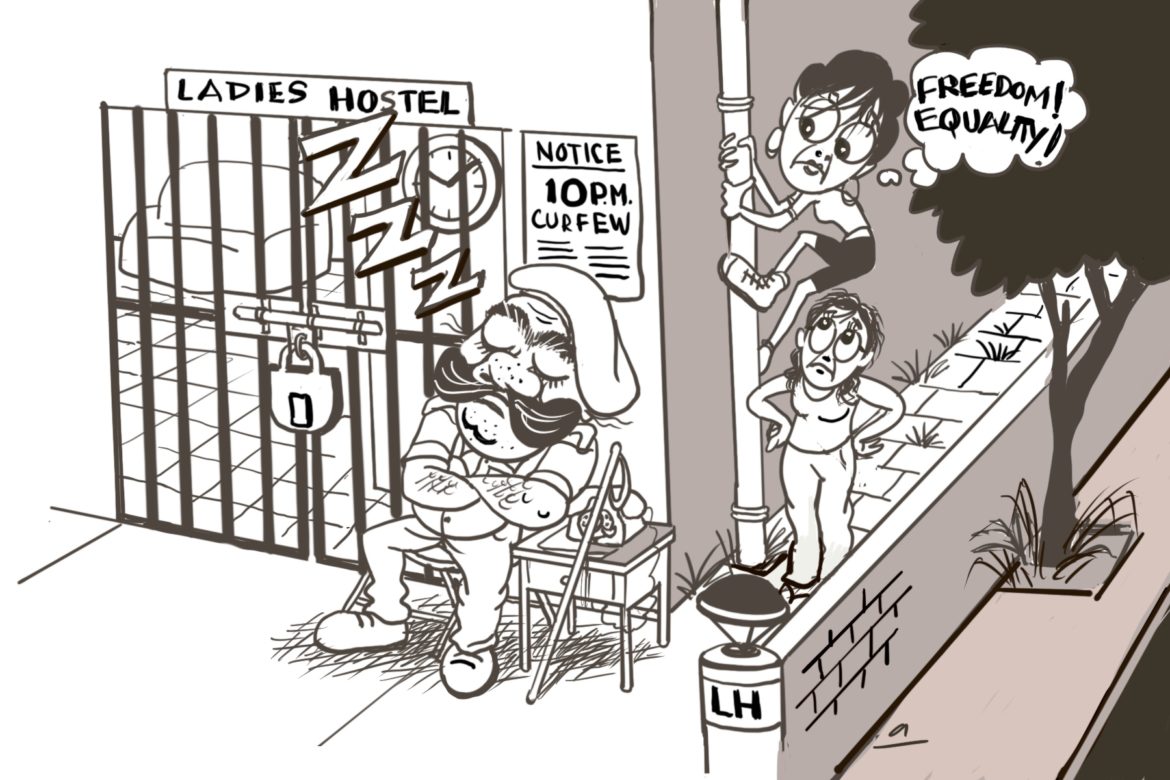

Little did they know how my seniors (among whom was one famous ‘hunterwali’) had fought against unfair restrictions. I had heard about it. I knew about the name change (LH to H10), the lifting of restrictions that were completely gender-biased, and the way these amazing girls had defied those restrictions. How they had climbed down water pipes and got out of the hostel after the gates were locked. So inspiring were these stories, that just for the fun of it I recall climbing down from the first-floor corridor using the pipe as support where needed.

But it was not simply about curfew. The rules, back in the early ’80s, may stun folks even now. Typically, men/boys are not allowed in a girls’/women’s hostel. Your dad/uncle/brother or (male)cousin/friend cannot visit your room. In H10 at IIT, boys could come in, provided they were met and escorted by a hostelite – fair enough! Why cannot classmates come to study or chat or play just because they happen to be of the opposite sex?

In H10, essentially, the atmosphere was a very healthy one of gender equality. Although I had come from a background where this would have been taken for granted, the fact that it was not so everywhere was a lesson. And that one had to question biases, could do so, and put an end to rules arising out of them, was the bigger lesson. And in some way, I have no doubt, this added to a sense of empowerment.

Fast forward to a few years later in an institute in Bangalore. I was staying in the hostel there. I had lots of friends, girls and boys, who would visit in the evening; we would sit out on the lawn or sometimes in my room and chat and plan weekend hiking/climbing trips. This, I later learned, did not go down well with many in the administration.

Unknown to us, they had put restrictions on visitors. I found out later because a friend was getting married and her mother had come to invite me to the wedding, card in hand. The security had stopped her at the gate to the small campus and said ‘no visitors after office hours’. Ridiculous! I was furious.

I marched to the admin officer to confront him about it. I do not recall all the details of that conversation but I do recall that he was sticking to that rule, but lamely. He said the rules were for my protection! I recall telling him I was well over 18 and he had no right to tell me what I should or should not do in my personal life – whether my friends could visit me or not. At last, he said he could do nothing, I should meet the Director. So off I went to meet the Director. And asked him some questions: Do you want social calls to take place during office hours? (Again) I am over 18, how can you restrict my life in my own free time? These questions had no answer, so he resorted to that great shield of government functioning: ‘It’s a security issue’. Ohh what a fantastic opening! Images of aunty going berserk with a gun and shooting down people who were on the campus ran through my mind. How is a 50-year-old woman who came with an invitation card for her daughter’s wedding a security threat, I asked. So finally he had to agree to my proposal: You can make a rule that the hostelite has to meet the visitor at the gate and thereafter is responsible for any security breach. I did not leave his office until he picked up the phone and instructed the Admin officer accordingly. It was as simple as that. Ask the right questions, and if there are no answers, ‘bakwas’ rules will get scrapped.

So the lessons learned subconsciously in the hostel came in handy every time I encountered situations that I saw as unfair. Had H10 accepted the rules meekly, I quite possibly might have thought ‘that’s the way it is’. But H10 had shown me that that was not the way it had to be! For that, I will always be grateful!